Showing posts with label Spike Lee. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Spike Lee. Show all posts

Friday, February 24, 2017

Nobody says "Huh?" like Denzel

This is the second of 12 or 13 blog posts that are being posted on a monthly basis from January 2017 until this blog's final post in December 2017.

Once upon a time, I ran an Internet radio station that streamed film and TV score music. I don't really miss running it. The audience for it dwindled over the years, and even though Live365, the Bay Area company that powered the station before the end of the Webcaster Settlement Act led to Live365's demise early last year, is being resuscitated, I don't have any plans to bring back the station.

But I've kept the station alive on Mixcloud, where I've archived a few hours of old station content and posted lots of new one-to-two-hour mixes of music from original scores. The most popular of those mixes has been a mix of Kyle Dixon/Michael Stein score cues from the first season of Netflix's unexpectedly popular Stranger Things. It's called "Where's Barb?"

Late last year, the score albums for the Magnificent Seven remake and the film version of Fences, which both star Denzel Washington, were sent to my inbox, and that made me want to edit together an entire mix of score cues from Denzel movies. Denzel has been one of my favorite actors, ever since he stole the 1989 white savior movie Glory (and won an Oscar for stealing it) in the same way Don Cheadle would later steal Devil in a Blue Dress from Denzel. In Glory, he was basically the Toshiro Mifune character from Seven Samurai: the shit-talking troublemaker and outsider who learns to channel his anger and penchant for self-destruction into a worthy cause and then (SPOILER!) dies a hero.

The late James Horner's score from that 1989 Civil War movie, Terence Blanchard's 1992 Malcolm X score and Hans Zimmer's 1995 Crimson Tide score are a trifecta of Denzel-related instrumental badassery. Put those three scores together in either a mix or an hour of radio programming, and that hour of music is automatically going to sound as rousing and badass as a Denzel speech. Procrastinating on a writing project or that load of laundry? Put on the badass "Fruit of Islam" from Malcolm X's classic hospital march sequence. Immediately after hearing "Fruit of Islam," shit is going to be done. Laundry is going to be washed.

This month is the perfect time to post a mix of score cues from Denzel flicks. Several of Denzel's most highly regarded movies are frequently recommended during Black History Month by the likes of film critics and librarians, and Fences, Denzel's third big-screen directorial effort, is up for a few Oscars this weekend. Viola Davis, who reprised a role she had alongside Denzel in one of the various stage versions of Fences, is the frontrunner for the Best Supporting Actress trophy.

Throughout the Mixcloud mixes, I like to drop audio clips from the movies or TV shows that I've selected for score cue airplay. For this Denzel mix, I could have gone with audio from Denzel speeches as the connective tissue between each Denzel movie score cue, but I decided to go with something even more brash as connective tissue: clips from the very funny Earwolf podcast Denzel Washington Is the Greatest Actor of All Time Period, hosted by stand-ups W. Kamau Bell, the host of the CNN documentary series United Shades of America, and Kevin Avery, a writer for Last Week Tonight.

Bell, Avery and a special guest Denzealot, whether it's another comedian, a black filmmaker or one of Denzel's previous co-stars, dissect the work of their favorite charismatic actor, with lots of humor and occasional jabs at things like Virtuosity (the poorly received 1995 Denzel cyber-thriller that pitted 'Zel against a murderous A.I. played by a pre-L.A. Confidential Russell Crowe) and Denzel's visible discomfort during Much Ado About Nothing's frolicking scenes. Denzel himself is aware of the podcast's existence. But I highly doubt he's ever going to be a guest on this podcast that both celebrates his many triumphs as an actor (as well as a director of both episodic TV and small-scale feature films) and dredges up Virtuosity-esque career missteps, and Denzel's recent Fences press junket comment about not wanting to live in the past confirmed it. The podcast doesn't just live in Denzel's big-screen (and small-screen) past. It raises kids and builds a whole garden of gladioli in his past.

Labels:

Crimson Tide,

Denzel Washington,

DJ AFOS,

film music,

Flight,

Glory,

Hans Zimmer,

James Horner,

Kevin Avery,

Malcolm X,

Oscars,

podcasts,

Spike Lee,

Terence Blanchard,

The Magnificent Seven,

W. Kamau Bell

Friday, January 30, 2015

Thanks to AFOS shuffle mode, I wonder what a Batman sandwich or a Star Trek sandwich would taste like

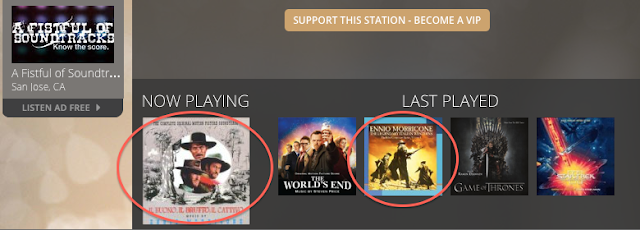

Even though it can occasionally be a hassle to try to keep track of 17 hours and 28 minutes of music, which is the average amount of music I calculated from the current total track lengths of the eight different playlists I keep in rotation for the "AFOS Prime" block (plus the extra hours of music that make up the five other blocks on the AFOS station schedule), running AFOS is a pretty simple task. I just hit "Shuffle" and Live365.com does the rest.

Often, weird things I have no control over take place during the shuffle mode I've set for AFOS, which is how I've regularly referred to the station since 2007. It's AFOS. No bloody FOS or FFOS. It's always been AFOS. I've always wanted to shorten the station name to just AFOS because the acronym evokes the four-call-letter names of the terrestrial radio stations I grew up listening to: KFRC, KMEL and so on. But instead of a K as the first letter, it's an A. Also, the acronym can stand for many different phrases besides A Fistful of Soundtracks, and I once jotted down a list of 12 of them. Examples include "Ample Focus on Scores," "All Fantastic Original Scores" and my personal favorite, "Asians Fucking Owning Shit."

Anyway, shuffle mode causes all these fantastic original scores to form either unintentional sets of two or three tracks by the same composer or "sandwiches," which is how I refer to cases where two tracks written by the same composer or emanating from the same movie or TV franchise appear to be sandwiching a completely unrelated track in the "last played" section of the AFOS Live365 site. I often take screen shots of these accidental sets or sandwiches.

Star Trek sandwiches happen frequently on AFOS. Mmm, Star Trek sandwich. I wonder how a Star Trek sandwich would taste. Maybe it would be like Chief O'Brien's "Altair sandwich" with no mustard from Deep Space Nine. Some Star Trek head who can't spell has defined an Altair sandwich as "three kinds of meet [sic], two cheeses, and any number of other additions." Whattup, future Super Bowl Sunday dish.

Batman sandwiches also happen a lot on AFOS. I wonder what a Batman sandwich would taste like. I figure it would be like the Batman Diner Double Beef at McDonald's in Hong Kong.

Hold up. An egg in a burger?! I hate eggs if they're not scrambled, and even though it's scrambled in this case, eggs don't belong in burgers. I'll pass.

Occasionally, there are spaghetti western sandwiches on "AFOS Prime." Is there such a thing as a spaghetti western sandwich? Apparently, there is. Somebody blogged about a spaghetti western sandwich shop in Rome. Some of its sandwiches are named after characters from Terence Hill and Bud Spencer's Trinity movies.

Here are more screen shots of shuffle mode weirdness I previously collected in 2011, joined by some new and never-before-posted screen shots of more weird music sandwiches and combinations.

Often, weird things I have no control over take place during the shuffle mode I've set for AFOS, which is how I've regularly referred to the station since 2007. It's AFOS. No bloody FOS or FFOS. It's always been AFOS. I've always wanted to shorten the station name to just AFOS because the acronym evokes the four-call-letter names of the terrestrial radio stations I grew up listening to: KFRC, KMEL and so on. But instead of a K as the first letter, it's an A. Also, the acronym can stand for many different phrases besides A Fistful of Soundtracks, and I once jotted down a list of 12 of them. Examples include "Ample Focus on Scores," "All Fantastic Original Scores" and my personal favorite, "Asians Fucking Owning Shit."

Anyway, shuffle mode causes all these fantastic original scores to form either unintentional sets of two or three tracks by the same composer or "sandwiches," which is how I refer to cases where two tracks written by the same composer or emanating from the same movie or TV franchise appear to be sandwiching a completely unrelated track in the "last played" section of the AFOS Live365 site. I often take screen shots of these accidental sets or sandwiches.

Star Trek sandwiches happen frequently on AFOS. Mmm, Star Trek sandwich. I wonder how a Star Trek sandwich would taste. Maybe it would be like Chief O'Brien's "Altair sandwich" with no mustard from Deep Space Nine. Some Star Trek head who can't spell has defined an Altair sandwich as "three kinds of meet [sic], two cheeses, and any number of other additions." Whattup, future Super Bowl Sunday dish.

Batman sandwiches also happen a lot on AFOS. I wonder what a Batman sandwich would taste like. I figure it would be like the Batman Diner Double Beef at McDonald's in Hong Kong.

|

| (Photo source: Geekologie) |

Occasionally, there are spaghetti western sandwiches on "AFOS Prime." Is there such a thing as a spaghetti western sandwich? Apparently, there is. Somebody blogged about a spaghetti western sandwich shop in Rome. Some of its sandwiches are named after characters from Terence Hill and Bud Spencer's Trinity movies.

|

| (Photo source: Afar) |

Here are more screen shots of shuffle mode weirdness I previously collected in 2011, joined by some new and never-before-posted screen shots of more weird music sandwiches and combinations.

|

| There have been unintentional time travel movie theme double shots. |

|

| Mel Gibson, who's so famously fond of Jews, gets followed by a Jew. |

|

| Yeah, I like "Eye of the Tiger" too, Live365, but I don't like it as much as you do apparently. |

|

| Same thing with the movie Wild Things... |

|

| ... or the end credits music from the first Thor flick. |

Labels:

A Fistful of Soundtracks,

Batman,

Bruce Lee,

Cowboy Bebop,

Drive,

film music,

Internet radio,

iTunes,

Jim Kelly,

Justin Lin,

Live365,

Michael Giacchino,

Pam Grier,

Shinichiro Watanabe,

Spike Lee,

Star Trek,

X-Men

Monday, June 30, 2014

"Motherfuck him and John Wayne!": Do the Right Thing turns 25

|

| Illustration by Xavier Payne |

When I first saw as a teen Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing, which turns 25 years old today, it was in the form of a heavily censored but still-provocative-for-network-TV version on CBS. Lee, who approved the CBS cut, had all the "motherfuckers" replaced with "mickey-fickey," a euphemism that never really caught on like, say for example, "shut the front door" has. Do the Right Thing's still-amazing (and still-misunderstood) "Fight the Power" theme, which was performed by the groundbreaking mickey-fickeys who make up Public Enemy, along with P.E.'s earlier track, the Yo! MTV Raps staple "Night of the Living Baseheads," helped get me hooked on hip-hop and made me interested in seeing the much-hyped movie that introduced "Fight the Power," even if it was in butchered form on CBS. ("Fight the Power," by the way, can be heard on AFOS, along with several of composer Bill Lee's score cues from the 1989 film.)

I didn't actually become a fan of Do the Right Thing until the second time I saw it, and this time, it was in its entirety and in the form of a copy one of my older brother's university housemates had of MCA/Universal Home Video's VHS release, which wasn't full of all those dubbed-in and distracting "mickey-fickeys" that meshed poorly with the frankness and rhythm of Lee's original dialogue. The then-controversial 1989 film floored me. I had never seen anything like it before.

Lee's open-ended and complex screenplay about both Bed-Stuy racial tensions, which mirrored real-life racially motivated violence in Bensonhurst and Howard Beach, and the moral dilemma over how to handle that kind of animosity, introduced me to a more cerebral and mature kind of cinema, where there are no clear-cut heroes and villains, and like life, not everything has a tidy ending. It's the same kind of cinema that, unfortunately, has become less common on the big screen--thanks to the post-1989 Batman flurry of tentpole franchises and superhero movies marketed to teens and adults who still act like teens--and more common on cable TV these days, whether it's in the form of original movies or original series.

Do the Right Thing helped improve my tastes in film, which tended to lean towards blockbusters like Tim Burton's Batman and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade before I got into Lee's work. The 1989 Lee Joint was my gateway to Lee's other joints, then to GoodFellas and other Martin Scorsese Pictures, and then to Chan Is Missing, Dog Day Afternoon and so on. Movies didn't have to dazzle me with just explosions and tits anymore. I learned to become dazzled by adult ideas and themes and--in the cases of Do the Right Thing and GoodFellas, another superb late '80s/early '90s New York movie that was robbed at the Oscars--brilliant dialogue and clever editing.

|

| Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee in Do the Right Thing |

|

| (Photo source: Miss Info) |

|

| (Photo source: Miss Info) |

|

| Illustration by Xavier Payne |

Labels:

A Fistful of Soundtracks,

Bill Lee,

Bill Nunn,

Brooklyn,

Do the Right Thing,

film music,

hip-hop,

NSFW,

opening titles,

Public Enemy,

Rosie Perez,

S. Craig Watkins,

Spike Lee,

Xavier Payne

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

"Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" will never be added to "Whitest Block Ever" rotation on AFOS, but I sure wish it could be

Pootie Tang, a Chris Rock Show spinoff movie featuring Lance Crouther's mostly unintelligible character from the late '90s HBO show, first played to empty theaters and negative reviews in 2001, but it turned out to be a lot funnier than expected and it gets referenced by rappers on the regular (Kanye West quoted Pootie during The College Dropout). Back in February, Prince Paul, the legendary producer of so many hip-hop albums I like, including De La Soul Is Dead and A Prince Among Thieves, posted on his SoundCloud an original song from Pootie Tang I had no idea he produced, the "Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" duet between Pootie and Missy Elliott.

At least once every month, I try to update an AFOS playlist like "The Whitest Block Ever" with new tracks, and I wish I could add "Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" to "The Whitest Block Ever." But no physical copies of "Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" exist (outside of I assume Prince Paul's studio). It's not even included on the out-of-print Pootie Tang soundtrack from Hollywood Records. Pootie Tang was written and directed by--and this still surprises people who aren't comedy nerds--Louis C.K., who wrote for The Chris Rock Show. The star/writer/showrunner/director/caterer of FX's Louie doesn't think much of Pootie Tang's final cut because Paramount wrested the movie away from him during post-production (and you can tell which parts of the movie were meddled with by the studio), but it's still a funny flick, thanks to moments like Prince Paul's dead-on parody of the slow jam genre.

"The Whitest Block Ever," a block of original themes or score cues from films written or directed by filmmakers of color, airs every weekday at 10am-noon on AFOS. Here's a sampler of "The Whitest Block Ever."

"The Whitest Block Ever" sampler tracklist

OPENING TITLES

1. Public Enemy, "Fight the Power" (from Do the Right Thing)

2. The Roots featuring Jaguar, "What You Want" (from The Best Man)

3. Eric B. & Rakim, "Juice (Know the Ledge)" (from Juice)

4. Adrian Younge featuring LaVan Davis, "Black Dynamite Theme"

5. Curtis Mayfield, "Freddie's Dead (instrumental version)" (from Superfly)

6. 2 Chainz and Wiz Khalifa, "We Own It (Fast & Furious)" (from Furious 6)

7. Stanley Clarke, "Passenger 57 Main Title"

8. Robert Rodriguez's Chingon featuring Tito & Tarantula, "Machete Theme"

9. The Gap Band, "I'm Gonna Git You Sucka"

10. The Staple Singers, "Let's Do It Again"

11. Mychael Danna, "Baraat" (from Monsoon Wedding)

12. Mychael Danna featuring Bombay Jayashri, "Pi's Lullaby" (from Life of Pi)

ACT 1

13. Brian Tyler, "Ready or Not" (from Finishing the Game)

14. E.U., "Da Butt" (from School Daze)

15. Curtis Mayfield, "Give Me Your Love (Love Song)" (from Superfly)

16. Rose Royce, "I Wanna Get Next to You" (from Car Wash)

17. Adrian Younge featuring Dionne Gipson, "Shine" (from Black Dynamite)

ACT 2

18. Guy, "New Jack City"

19. Brian Tyler, "Fists of Führer" (from Finishing the Game)

20. Semiautomatic, "Eat with Your Eyes" (from Better Luck Tomorrow)

21. George Shaw, "Date Chase" (from Agents of Secret Stuff)

22. Mychael Danna, "Set Your House in Order" (from Life of Pi)

23. Branford Marsalis Quartet, "Mo' Better Blues"

ACT 3

24. Ramin Djawadi, "Canceling the Apocalypse" (from Pacific Rim)

25. Bill Lee, "Wake Up Finale" (from Do the Right Thing)

26. Bill Lee, "Malcolm and Martin" (from Do the Right Thing)

END TITLES

27. Sukhwinder Singh, "Aaj Mera Jee Kardaa (Today my heart desires)" (from Monsoon Wedding)

28. Mader, "Rhumba (End Credits)" (from The Wedding Banquet)

29. Curtis Mayfield, "Superfly"

30. Blake Perlman featuring RZA, "Drift" (from Pacific Rim)

31. The Crooklyn Dodgers featuring Special Ed, Buckshot and Masta Ace, "Crooklyn"

At least once every month, I try to update an AFOS playlist like "The Whitest Block Ever" with new tracks, and I wish I could add "Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" to "The Whitest Block Ever." But no physical copies of "Tipi Ti on My Cappi Town" exist (outside of I assume Prince Paul's studio). It's not even included on the out-of-print Pootie Tang soundtrack from Hollywood Records. Pootie Tang was written and directed by--and this still surprises people who aren't comedy nerds--Louis C.K., who wrote for The Chris Rock Show. The star/writer/showrunner/director/caterer of FX's Louie doesn't think much of Pootie Tang's final cut because Paramount wrested the movie away from him during post-production (and you can tell which parts of the movie were meddled with by the studio), but it's still a funny flick, thanks to moments like Prince Paul's dead-on parody of the slow jam genre.

"The Whitest Block Ever," a block of original themes or score cues from films written or directed by filmmakers of color, airs every weekday at 10am-noon on AFOS. Here's a sampler of "The Whitest Block Ever."

"The Whitest Block Ever" sampler tracklist

OPENING TITLES

1. Public Enemy, "Fight the Power" (from Do the Right Thing)

2. The Roots featuring Jaguar, "What You Want" (from The Best Man)

3. Eric B. & Rakim, "Juice (Know the Ledge)" (from Juice)

4. Adrian Younge featuring LaVan Davis, "Black Dynamite Theme"

5. Curtis Mayfield, "Freddie's Dead (instrumental version)" (from Superfly)

6. 2 Chainz and Wiz Khalifa, "We Own It (Fast & Furious)" (from Furious 6)

|

| Car Wash (Photo source: Rated X - Blaxploitation & Black Cinema) |

8. Robert Rodriguez's Chingon featuring Tito & Tarantula, "Machete Theme"

9. The Gap Band, "I'm Gonna Git You Sucka"

10. The Staple Singers, "Let's Do It Again"

11. Mychael Danna, "Baraat" (from Monsoon Wedding)

12. Mychael Danna featuring Bombay Jayashri, "Pi's Lullaby" (from Life of Pi)

ACT 1

13. Brian Tyler, "Ready or Not" (from Finishing the Game)

14. E.U., "Da Butt" (from School Daze)

15. Curtis Mayfield, "Give Me Your Love (Love Song)" (from Superfly)

16. Rose Royce, "I Wanna Get Next to You" (from Car Wash)

17. Adrian Younge featuring Dionne Gipson, "Shine" (from Black Dynamite)

ACT 2

18. Guy, "New Jack City"

19. Brian Tyler, "Fists of Führer" (from Finishing the Game)

|

| Better Luck Tomorrow (Photo source: RECO CHARGES) |

21. George Shaw, "Date Chase" (from Agents of Secret Stuff)

22. Mychael Danna, "Set Your House in Order" (from Life of Pi)

23. Branford Marsalis Quartet, "Mo' Better Blues"

ACT 3

24. Ramin Djawadi, "Canceling the Apocalypse" (from Pacific Rim)

25. Bill Lee, "Wake Up Finale" (from Do the Right Thing)

26. Bill Lee, "Malcolm and Martin" (from Do the Right Thing)

END TITLES

27. Sukhwinder Singh, "Aaj Mera Jee Kardaa (Today my heart desires)" (from Monsoon Wedding)

28. Mader, "Rhumba (End Credits)" (from The Wedding Banquet)

29. Curtis Mayfield, "Superfly"

30. Blake Perlman featuring RZA, "Drift" (from Pacific Rim)

31. The Crooklyn Dodgers featuring Special Ed, Buckshot and Masta Ace, "Crooklyn"

Monday, August 5, 2013

Uwe Boll's essential film list

Respected and controversial filmmaker Spike Lee, who directed several favorite movies of mine (Do the Right Thing, Inside Man), also teaches film at his alma mater NYU. At the start of each semester, Professor Lee hands out to his film students a list of movies he's selected as essential viewing. The list went viral after Lee posted it last week over at his much-debated Kickstarter page for his next joint, a horror genre project he's had some trouble getting off the ground (half of the list is posted below).

Some people have beefs with Lee's list of his favorite films. The Women and Hollywood blog noted that only one of Lee's picks was directed by a woman (City of God, which was co-directed by Kátia Lund), while a Racialicious writer tweeted that she read a complaint from another writer of color about Lee's list being too white. Whatever the case though, Lee's list is full of intriguing choices (Kung Fu Hustle? Fuck yeah!) and a lot of movies that are worth experiencing again (Kung Fu Hustle!).

Did you know Uwe Boll teaches film as well? I happened to procure a copy of Boll's essential film list.

[via University of Phoenix]

Some people have beefs with Lee's list of his favorite films. The Women and Hollywood blog noted that only one of Lee's picks was directed by a woman (City of God, which was co-directed by Kátia Lund), while a Racialicious writer tweeted that she read a complaint from another writer of color about Lee's list being too white. Whatever the case though, Lee's list is full of intriguing choices (Kung Fu Hustle? Fuck yeah!) and a lot of movies that are worth experiencing again (Kung Fu Hustle!).

Did you know Uwe Boll teaches film as well? I happened to procure a copy of Boll's essential film list.

[via University of Phoenix]

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

"'Kid' spelled backwards describes you best": A look at each track in the newest "Whitest Block Ever" playlist on AFOS

"The Whitest Block Ever," a new AFOS block that I added to the station schedule as a way to mark Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (the block will remain on the schedule after May), is actually made up of five different one-hour playlists (and hopefully six, if Live365 hard drive space will allow it, and perhaps with an original track from Furious 6). All five playlists contain original themes and score cues from films done by Asian American directors and other filmmakers of color who have worked on films or TV series episodes I've dug or admired. "The Whitest Block Ever" airs every weekday at 10am-noon on AFOS.

Last week, I finished assembling the fifth playlist, a.k.a. "TheWhitestBlockEver05" (all the tracks in "TheWhitestBlockEver05" are streamed only during the "Whitest Block Ever" block and nowhere else on the station schedule, in order to reduce repetition). I enjoyed reading the replies Edgar Wright and "Whitest Block Ever" playlist fixture Robert Rodriguez gave to Empire magazine about their favorite score cues or soundtrack albums in the magazine's soundtrack tribute issue, so in a fashion similar to what Wright and Rodriguez did for Empire, here are descriptions of each of the 13 tracks in "TheWhitestBlockEver05."

1. Elmer Bernstein, "Prologue" (from Hoodlum)

Man, Bernstein could do it all: from slapstick vehicles for SNL alums like Trading Places and Ghostbusters to Harlem period pieces like the Bill Duke films A Rage in Harlem and Hoodlum. The ondes Martenot, an electronic instrument that Bernstein utilized most memorably in his Ghostbusters score and can easily be mistaken for a theremin, pops up in "Prologue" too and was used to great effect to represent an era of Harlem gone by.

2. Keisa Brown, "Five on the Black Hand Side" (from Five on the Black Hand Side)

I've seen only bits and pieces of this 1973 film, which has an enjoyable opening theme penned by legendary Capitol Records soul arranger H.B. Barnum and an equally enjoyable shot-on-a-shoestring trailer. The marketing for Five on the Black Hand Side brashly asserted that the film, an adaptation of a comedic stage play about the clash between Afrocentricism and black conservatives, was an alternative to the violent blaxploitation fare that was popular at the time of the film's release. "You've been Coffy-tized, Blacula-rized and Superfly-ed. You've been Mack-ed, Hammer-ed, Slaughter-ed and Shaft-ed. Now we wanna turn you on to some brand new jive," proclaims Fun Loving (Tchaka Almoravids) in the trailer. "You're gonna be glorified, unified and filled with pride when you see Five on the Black Hand Side."

3. Kid 'N Play, "Kid vs. Play (The Battle)" (from House Party)

I wish the Obama/Romney and Biden/Ryan debates were more like the freestyle battle scenes in 8 Mile and House Party.

4. Mader, "Rhumba (End Credits)" (from The Wedding Banquet)

Gentle-humored comedies about generational discord within families (or survival dramas about orphans who find unlikely surrogate families in the form of tigers) are where Taiwanese-born Ang Lee, this year's Best Director Oscar winner for Life of Pi, works best, not action material that calls for a nimbler touch from someone like Tsui Hark or Joss Whedon, like Lee's 2003 misfire Hulk. (As Stop Smiling said in its amusing evisceration of the two pre-Mark Ruffalo Hulk movies, "Lee shouldn’t do pop; his attempts to 'enliven' the material and make it more like a comic book with screen panels and visible page breaks was the cinematic equivalent of Karl Rove dancing.") Over a decade before he won his first Oscar for directing Brokeback Mountain, Lee tackled LGBT characters in The Wedding Banquet, a standout piece of Asian American indie cinema about Wai-Tung (Winston Chao), a Taiwanese American landlord who, with the prodding of his boyfriend Simon (Mitchell Lichtenstein), marries Wei-Wei (May Chin), a struggling Chinese artist, to enable her to get a green card and to satisfy his traditionalist parents from Taiwan. I feel like The Wedding Banquet has kind of been overlooked during this Brokeback/Life of Pi period of Lee's career, despite having been the most profitable film of 1993, even more so than Jurassic Park (it also went on to spawn a stage musical version in 2003). On paper, The Wedding Banquet reads like a shitty sitcom. But the film is far from being such a thing, thanks to Lee's thoughtful and low-key direction, which is aided by French-born composer Mader's equally low-key score, a mishmash of Chinese and Latin sounds that (spoilers!) mirrors how the future child of Wai-Tung, Simon and Wei-Wei will grow up to be a mishmash of various cultural influences.

5. Melba Moore, "Black Enough" (from Cotton Comes to Harlem)

I had no idea Galt MacDermot, one of the most frequently sampled composers in hip-hop, scored Cotton Comes to Harlem until recently. I've seen the Ossie Davis-directed adaptation of the Chester Himes novel of the same name two or three times, but that was before I became interested in finding out where beatmakers copped so many of their illest samples from (it's also kind of hard to notice MacDermot's musical trademarks during Cotton Comes to Harlem when all your 19-year-old self can think about is the film's T&A, like Judy Pace's T&A when she ducks out of being kept under watch by a dumb white cop by craftily tricking him into bed without sleeping with him). One of my favorite MacDermot samples takes place during 9th Wonder & Buckshot's "Shinin' Y'all," which loops "Sunlight Shining," a tune that happens to come from Cotton Comes to Harlem. I'd like to see some beathead make use of another Cotton Comes to Harlem joint, "Black Enough," the film's opening theme, which, like "Sunlight Shining," is filled with soothing strings and classic MacDermot beats.

6. Michael Jackson, "On the Line" (from Get on the Bus)

It's been a few years since I watched Spike Lee's Million Man March-themed Get on the Bus, so I forgot that Michael Jackson sung the film's opening title theme, which contains lyrics about overcoming self-hatred that bring to mind the Five on the Black Hand Side theme (and the Jackson theme was produced by Babyface too!). "On the Line" is, along with "Butterflies" and maybe the Teddy Riley-produced "Remember the Time," one of the few tunes from Jackson's post-Bad, extremely treacly "won't someone think of the children?" era that I actually like. The fact that "On the Line" is--like Everybody Loves Raymond used to say at the start of each episode--not really about the kids also helps.

Friday, February 22, 2013

AFOS Blog Rewind: Do the Right Thing (Part 5 of 5)

It's Black History Month, so all this week, I've been reposting every single past AFOS blog post about one of my favorite films, Do the Right Thing, the timeless and still-bracing 1989 Spike Lee Joint. You can hear original score (or original song) selections from Do the Right Thing on AFOS.

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Parts 1, 2, 3 and 4. The following is from April 4, 2012.)

Laura K. Warrell's 2002 Salon article about Public Enemy's "Fight the Power"--which the group wrote for Do the Right Thing after Spike Lee abandoned his early idea of having Rosie Perez dance to The Capitols' "Cool Jerk" in the opening titles--excellently elucidates the P.E. track's impact on hip-hop, as well as pop music that means something more than the first four things in Elvis Costello's line about how songs are about five subjects ("I'm leaving you. You're leaving me. I want you. You don't want me. I believe in something.").

But Warrell's proclamation that conscious hip-hop is dead was premature. It's still out there. You just have to know where to look:

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Parts 1, 2, 3 and 4. The following is from April 4, 2012.)

|

| (Photo source: The Criterion Contraption) |

But Warrell's proclamation that conscious hip-hop is dead was premature. It's still out there. You just have to know where to look:

Like “Do the Right Thing,” the Spike Lee film to which it was tied, the song broke at a crucial period in America’s struggle with race, capturing both the psychological and social conflicts of the time. Unabashedly political, “Fight the Power” was confrontational in the way great rock has always been. It had the kind of irreverence that puts bands on FBI lists. “Fight” demanded action and, as the band’s most accessible hit, acted as the perfect summation of its ideology and sound. Every kid in America, white, black or brown, could connect to the song’s uncompromising cultural critique, its invigoratingly danceable sound and its rallying call.

And who could blame them? Ultimately, parachute pants and Flock of Seagulls haircuts couldn’t quell the frustrations of the Me Decade. The presidential tag team of Ronald Reagan and George Bush Sr. had dismantled a battery of social programs, squashing urban communities already struggling with poverty, guns and violence. Crack ravaged the inner city. AIDS rocked the nation. Black leaders, including Jesse Jackson, tried to bathe America’s race problem in as bright a spotlight as possible. The artistic community, already defiant in the face of Reagan-era conservatism, became even more provocative. The ’80s gave us Robert Mapplethorpe, the U2 of “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” Darling Nikki…

From inside the storm, Chuck D comes out swinging, verbally hacking into scraps a roster of American icons: “Elvis was a hero to most/ But he never meant shit to me, you see/ Straight up racist that sucker was simple and plain/ Motherfuck him and John Wayne.” Arguably the most fearless lyric in all of popular music, this anti-ode to Elvis and John Wayne is a virtual flag-burning. Who better embodies the American ideal than Duke and the King, bumbling patriots who personified the nation’s illiberal character and defended its order, an order from which blacks had been routinely barred? Chuck D cutting them up so brazenly was like a spiritual emancipation for anyone who felt excluded from American culture. In making a mockery of two of the country’s greatest heroes, P.E. assailed white America’s fairy-tale world and boldly accepted their place at its margins.

Thursday, February 21, 2013

AFOS Blog Rewind: Do the Right Thing (Part 4 of 5)

It's Black History Month, so all this week, I'm reposting every single past AFOS blog post about one of my favorite films, Do the Right Thing, the timeless and still-bracing 1989 Spike Lee Joint. You can hear original score (or original song) selections from Do the Right Thing on AFOS.

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Parts 1, 2 and 3. The following is from August 25, 2009.)

After posting a bunch of interesting Batman concept drawings and set photos from the 20-year-old blockbuster's official movie souvenir magazine, I'm doing the same thing with a similar tie-in for summer 1989's other landmark film, Do the Right Thing. But instead of an official movie mag, the Spike Lee Joint spawned a now-out-of-print Fireside/Simon & Schuster companion book that Lee wrote with the assistance of ex-girlfriend Lisa Jones. The director has done several companion books for his films. Each of these books contain behind-the-scenes photos, the film's script and Lee's own production journal (some of the Do the Right Thing journal passages are like tweets with better spelling: "Haven't written in a couple of days. I've been busy trying to save School Daze from being dogged.").

I've discussed before why Do the Right Thing is one of my favorite films and why writers of color like myself cite it as an influence. One aspect of the film that I don't think gets enough props is the terrific production design by Wynn Thomas, who drew this sketch of the We Love Radio and Sal's Famous Pizzeria set exteriors. Using an old Coney Island pizzeria as the basis for Sal's, the film's crew built it from scratch on an empty Bed-Stuy lot. "The ultimate compliment was when real people would walk off the street and try and buy a slice," said Thomas in an L.A. Times oral history about the movie. Thomas later created nifty-looking sets for Mars Attacks! and brought CONTROL Headquarters into the 21st century for Steve Carell's Get Smart.

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Parts 1, 2 and 3. The following is from August 25, 2009.)

After posting a bunch of interesting Batman concept drawings and set photos from the 20-year-old blockbuster's official movie souvenir magazine, I'm doing the same thing with a similar tie-in for summer 1989's other landmark film, Do the Right Thing. But instead of an official movie mag, the Spike Lee Joint spawned a now-out-of-print Fireside/Simon & Schuster companion book that Lee wrote with the assistance of ex-girlfriend Lisa Jones. The director has done several companion books for his films. Each of these books contain behind-the-scenes photos, the film's script and Lee's own production journal (some of the Do the Right Thing journal passages are like tweets with better spelling: "Haven't written in a couple of days. I've been busy trying to save School Daze from being dogged.").

I've discussed before why Do the Right Thing is one of my favorite films and why writers of color like myself cite it as an influence. One aspect of the film that I don't think gets enough props is the terrific production design by Wynn Thomas, who drew this sketch of the We Love Radio and Sal's Famous Pizzeria set exteriors. Using an old Coney Island pizzeria as the basis for Sal's, the film's crew built it from scratch on an empty Bed-Stuy lot. "The ultimate compliment was when real people would walk off the street and try and buy a slice," said Thomas in an L.A. Times oral history about the movie. Thomas later created nifty-looking sets for Mars Attacks! and brought CONTROL Headquarters into the 21st century for Steve Carell's Get Smart.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

AFOS Blog Rewind: Do the Right Thing (Part 3 of 5)

It's Black History Month, so all this week, I'm reposting every single past AFOS blog post about one of my favorite films, Do the Right Thing, the timeless (except for Radio Raheem's boombox and "Dump Koch") and still-bracing 1989 Spike Lee Joint. You can hear original score (or original song) selections from Do the Right Thing on AFOS.

It's Black History Month, so all this week, I'm reposting every single past AFOS blog post about one of my favorite films, Do the Right Thing, the timeless (except for Radio Raheem's boombox and "Dump Koch") and still-bracing 1989 Spike Lee Joint. You can hear original score (or original song) selections from Do the Right Thing on AFOS.(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Parts 1 and 2. The following is from July 1, 2009.)

Do the Right Thing caused quite a stir at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, dividing the audience, the jurors and the guest filmmakers. German filmmaker and Cannes juror Wim Wenders complained that Mookie was not enough of a hero for throwing the trash can in the film's climax. Later on, star/director Spike Lee would say that somewhere in his closet is a baseball bat with Wenders' name on it.

When the film was first released, some critics feared it would incite black moviegoers to riot or start fights in the theaters, while more open-minded critics praised it for its ambiguity. Desson Thomson of the Washington Post called Do the Right Thing radical filmmaking at its best, and Roger Ebert said "it comes closer to reflecting the current state of race relations in America than any other movie of our time... this movie is more open-ended than most. It requires you to decide what you think about it... Do the Right Thing doesn't ask its audiences to choose sides; it is scrupulously fair to both sides, in a story where it is our society itself that is not fair."

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association was as equally awed by Do the Right Thing, and they awarded the film with Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (for Danny Aiello as Sal) and Best Music honors. Meanwhile, the Oscars acted like the film didn't exist, although it was nominated for Aiello's performance and Lee's screenplay. In one of the most memorable moments from the Oscar telecast that year, a nervous and trembling Kim Basinger criticized the Academy for snubbing Do the Right Thing, which she called "the film that might tell the biggest truth of all." Barely anybody applauded, but Lee, who was in the audience, passed on a note of thanks to Basinger after her shout-out.

This week, Do the Right Thing makes its debut on Blu-ray with a few more extras than the already fully loaded 2001 Criterion DVD. This series of partial transcripts of segments from A Fistful of Soundtracks' 1999 episode about one of my favorite films concludes with more comments from S. Craig Watkins, the author of Hip Hop Matters: Politics, Pop Culture and the Struggle for the Soul of a Movement (Beacon Press, 2005), and Mark A. Reid, the editor of Cambridge Film Handbooks' volume on Do the Right Thing (Cambridge University Press, 1997), whom I interviewed separately for the show.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jimmy J. Aquino: Let's talk about Spike Lee's portrayals of the white characters in Do the Right Thing. What fascinates you about these characterizations?

S. Craig Watkins: What's really interesting about Spike's representation of whiteness is a number of things. I think that was the first of his feature films that actually involved white characters. Prior to that, most of his movies had been all-black casts, all-black-themed types of movies. So one of the questions that was actually posed to him as Do the Right Thing was being released was "Spike, how was it trying to direct white actors? How was it trying to write characters who are white?" The presumption for having that question was that a black filmmaker really had little of any knowledge or familiarity with whiteness, so therefore, he or she would have difficulty imagining, creating and directing white characters. Obviously, there's some sort of racial implications embedded in that in terms of... It's okay, I guess... White filmmakers are never asked, "Well, how is it creating or directing a black character?" So the question then is "Why is it that black filmmakers should have difficulty?," particularly given the sort of savvy ways in which blacks see, experience and understand whiteness in our society today anyway.

The other interesting thing about Spike Lee and his representation of whiteness and the white characters in the movie is that Sal is by far the most fully developed character in that movie, in terms of being a well-rounded, three-dimensional character. We see multiple sides of whiteness, multiple kinds of conflicting values around race, class, community, pride and ethnicity that are articulated via Sal's character. In that sense, it really showed how Spike on occasion is able to create very interesting, very nuanced types of characters.

The other thing too that I thought was very important about his portrayal of whites in that movie is I think it would have been very easy for Spike Lee and later African American filmmakers to play on what we might call counterracial stereotypes of whites, and that is depicting whites as the villains, in very one-dimensional, flat ways. I think what he was able to do in Do the Right Thing is to show and suggest that there are multiple ways in which whiteness gets expressed. There are multiple racial attitudes that white Americans develop. So in that sense, the way in which each of the white characters in the movie--and I'm talking specifically about Sal the father and his two sons--they all in some ways represented very different kinds of white racial sensibilities, white racial experiences and white relationships to blacks and blackness.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reid explains why Lee's perspective gave Do the Right Thing an edge over other films about race relations.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

JJA: How does Do the Right Thing succeed in its portrayal of racial animosity and racism, whereas other films about racism have failed?

Mark A. Reid: Like what other films would you say have failed?

JJA: Not so much as failed, but more problematic. For instance, films that portray tumultuous episodes in African American or African history, but it's really the story about the white friend of the black leader.

MAR: Oh, those types of films. I see. I think it's very important that a black directed the film. I'm not saying that any film directed by a black is going to be successful about portraying racism, but I think it's very important that Spike Lee's an African American. I think it's important also, to add on to that, that he's an African American that is aware of racism. In his film, the active characters are not just white people. It's very important to have a large swipe of different types of blacks that are involved, as opposed to one unique black and maybe two or three whites. I think that's what Spike Lee films do. They activate those blacks who are involved...

When you think of... Who Killed Vincent Chin? I don't think a white person could have made that film. I know somebody's going to call me an essentialist. I think at that point in time, when that film was made, I think it was very important that an Asian person made the film--and an Asian person who's talented, just like Spike Lee. Although he has a lot of flaws, he's a very talented filmmaker, and his language is well-versed in black culture.

I think it comes down to that--who the director and the writers are, when you work in a collective where you have mixed people, and you listen to all their different cultural stories and languages, to create a film... Because when Spike Lee made that film, his Italian American stars wrote a lot of what they'd say, and if they didn't believe in what they were doing, they'd say, "You know, we should do it this way." Spike Lee was a strong enough director to accept that. I think that's very important. Although I think he had a problem dealing with that in Jungle Fever, when Annabella Sciorra... I think he was unable to accept her reading of that relationship. But I think he's a director that's able to work with actors and be led by them sometimes.

JJA: Mark Reid, thank you.

MAR: Oh, you're welcome very much, and I enjoyed this. I learned something.

JJA: What did you learn?

MAR: That I didn't know that much about Spike Lee's films. [A woman in Reid's office can be heard laughing in the background.]

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

AFOS Blog Rewind: Do the Right Thing (Part 2 of 5)

It's Black History Month, so all this week, I'm reposting every single past AFOS blog post about one of my favorite films, Do the Right Thing, the timeless (except for Radio Raheem's boombox and "Dump Koch") and still-bracing 1989 Spike Lee Joint. You can hear original score (or original song) selections from Do the Right Thing on AFOS.

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Part 1. The following is from July 1, 2009.)

"I've been listening to 'Cool Jerk' by the Capitols. It's a real classic, fast and upbeat, and it brings to mind summer in the city. This may be the song for the opening credits sequence. I see Rosie Perez dancing to 'Cool Jerk' all over Brooklyn at the first heat of dawn. Rosie doing the Cool Jerk on the Brooklyn Bridge, on the promenade, and on various rooftops."

--Spike Lee, the May 17, 1988 entry in his production journal, Do the Right Thing (Fireside Books, 1989)

Do the Right Thing wouldn't have been the same without Public Enemy's rousing and confrontational original song, "Fight the Power." I can't imagine the film opening with Lee's earlier choice of "Cool Jerk." The series of excerpts from my 1999 A Fistful of Soundtracks interviews with African American Do the Right Thing experts continues with a discussion with S. Craig Watkins, a UT Austin professor of sociology, African American studies and radio-television-film, about one of the film's most powerful and effective elements, its soundtrack.

The Do the Right Thing soundtrack consisted of original songs by artists ranging from P.E. to Take 6 and a Copland-esque original jazz score composed by Lee's father Bill and performed by the Natural Spiritual Orchestra, which you can hear selections from on the Fistful of Soundtracks channel. For the film, Bill Lee assembled a septet that included saxman Branford Marsalis and trumpeter Terence Blanchard (who later became Lee's regular composer), as well as a 48-piece string section.

Jimmy J. Aquino: Although Do the Right Thing was a pivotal moment in black cinema, the mainstream films directed by African Americans in the next couple of years were from the gangsta genre instead of being influenced by the Spike Lee Joints, which were more cerebral. Why was that so?

S. Craig Watkins: Much of black cinema, I would argue, tends to be influenced by what's happening in black popular music. In Do the Right Thing, you see Spike using a number of different kinds of black musical genres, styles and traditions. The one song that really, really drives the movie and I think is the most remembered is the song "Fight the Power" by Public Enemy, which is playing into this kind of hyper-racialized neo-black nationalist politics that were taking place during that time, and so he features that and uses that as the energy that drives his movie. But as that's happening, at the same time, we see in 1988/1989/1990 a new trend taking place within the field of black American popular music, more specifically rap music, in terms of the emergence of gangsta rap, and what we see eventually in the film industry, again tapping into that same energy, tapping into that same vibe, tapping into what gangsta rap was saying, doing and how it was resonating with consumers. So we see the movies also turning more and more in that direction...

JJA: Is there anything else that you find intriguing about Spike Lee's use of music in Do the Right Thing?

SCW: Yeah, one of the things I like to say in terms of giving Spike Lee some props regarding his movies is that he's always understood that black musical styles and traditions have a long history, a long legacy and are very diverse. Compare, for example, soundtracks that were typically associated with a lot of popular action ghetto-themed movies throughout the 1990s. Most of these soundtracks are most exclusively gangsta rap music, hardcore, harder-edged kind of music, which in some ways, don't necessary illuminate the complex and rich history of black music.

On the other hand, soundtracks that Spike Lee generally compiled for his movies--and Do the Right Thing is a perfect example--you've got your traditional R&B songs on there, a reggae-style joint on there, you have the rap music by Public Enemy, you have the black female rhythm and blues tradition... He did a jazz score for the movie and subsequently released a jazz score CD. So my main point is that Do the Right Thing, that soundtrack, as well as a number of his other films--particularly School Daze comes to mind--he draws from a broad cross-section of black musical traditions, tapping into an understanding, just how complex, diverse and dynamic black American music has been.

Not all the films we love are perfect. The Cambridge Film Handbooks volume on Do the Right Thing that UF Gainesville English professor Mark A. Reid edited is a compilation of essays that both praise and critique Lee's controversial film. The book also reprints film critics' reviews of Do the Right Thing from the summer of 1989. During A Fistful of Soundtracks' 1999 episode about Do the Right Thing, I wanted to hear from Reid what he thought were the film's merits and if there was anything that was missing from Lee's depiction of 1989 Bed-Stuy.

JJA: In the film's portrayal of Bed-Stuy and the interracial tensions... is there anything in this portrayal of racial politics that it overlooks?

Mark A. Reid: Well, one would have to know the Bedford-Stuyvesant area pretty well to be able to say that it overlooks it, but I think it gives an ample picture of the different types of African Americans that live there. You have the West Indians and the different types, and you have the African Americans. You have the fact that there are Korean shopkeepers. Perhaps when Spike was younger, they weren't Korean. They were probably either Jewish or maybe Arab. The fact that there's gentrification going on in Bed-Stuy. But gentrification isn't always white yuppie. It's also buppies. We can see that in Jungle Fever, when in fact, the people who live in that area--and I think it's Harlem--the people that gentrified that area, and they're all upwardly mobile African American couples. You do have the hanger-on who's probably been there a long time... and you have different types of reactions by this Italian American family. I think that's interesting.

You don't get much of an art community around there, and I think there is a black art community that developed because they couldn't afford to live in Manhattan. You don't get the fact that there's drugs, and everybody has criticized him for that. I think if he introduced that, he'd have to develop it, and it would probably overtake the story he's trying to tell...

Do the Right Thing, although it's interesting and everything, I still think it's a very thin film. I think it's an important film because politically, how it was used when it came out and what is criticized in the film, not only Koch, but the brutality that some law officers--although that, I think, was an accident--they abuse their power. It does talk about the tension that was mounting, that would later erupt, and not only in Bedford-Stuyvesant, but in Los Angeles, the trial of Rodney King. It's like a marker. It sees certain things that are happening in the urban situation between blacks and other ethnics. Because ultimately, it did happen between the Korean businesspersons in Los Angeles.

JJA: And also, years before in New York, there were conflicts between the Korean shopkeepers and the blacks.

MAR: Right. But the thing is that what would have been interesting is that also--which is I guess it's hard to do in most films since you have a singular narrative that dominates a film--is that it's very important to understand who those Koreans are and their culture, and that's what we don't get. If Koreans come from a culture where you don't touch people when you're handing back the money or other things, and other people who aren't Korean read it differently, then there's a miscommunication, and it's on both parts, the Koreans and whoever the other community is, be it African American or Mexican American or whatever. It would be interesting to have a film that dealt with that and dealt with what Do the Right Thing did.

Watkins explains why even some black viewers thought Do the Right Thing fell short.

SCW: I would argue that the problem with Do the Right Thing in retrospect is that it also illuminated some of the limitations with the kind of racial politics, the racial ideology, that the movie both played on and used as a driving and narrative force. Some thought that it was a bit overdone, in terms of the black racial politics. Some thought that the black racial politics were articulated in ways that weren't either nuanced or very sophisticated, in terms of the kinds of characters who were the leading proponents of a prism of the black progressive agenda. Here, I'm talking about, for example, the character of Buggin' Out, who many argue--and I think accurately so--was basically more of a caricature than a character per se.

I asked Reid about some black viewers' gripes with Giancarlo Esposito's Buggin' Out character.

JJA: There's this interesting criticism about Buggin' Out, that Spike Lee's portrayal of Buggin' Out is a mockery of black political activism.

MAR: It's a mockery in a sense that what Buggin' Out wants to do is boycott Sal's, as opposed to... In the history of African Americans, we boycott, and we also choose another alternative to Sal at the same time. What Buggin' Out wants to do is change pictures, which really doesn't mean that much. It's superficial.

JJA: It's about image.

MAR: Right. Why wouldn't he say, "Hire more people from the community"? Why wouldn't he help support somebody else who wants to build a small restaurant and teach them--an internship? That's what a boycott could do. A boycott to change photographs on a wall? "You put up Muhammad Ali and you put up a basketball player"? So what? That's decoration.

But even within the film, the characters didn't take Buggin' Out that seriously. Spike Lee using those characters and taking that not so seriously means that they're waiting for a more serious type of political activism than what Buggin' Out offers them. So I wouldn't look at it totally as a critique of black activism. I'd look at it as a critique of a certain type of black activism, which might, in fact, be a critique of Al Sharpton. That hasn't ever been discussed, but you could see that at that point in time. I don't know what "Tawana Told the Truth" means. Are we supposed to take it seriously or is it like a critique of the Tawana Brawley thing? That's the problem too... But the thing is that do we want a conclusive "Yes, this is what it's about"? Or do we want to be forced to think about these issues? I think that maybe that's what Spike Lee is doing.

Watkins offers his take on the film's open-endedness.

JJA: Another intriguing aspect about Do the Right Thing is the narrative techniques. What's unconventional about these narrative techniques?

SCW: What Spike does in Do the Right Thing in some ways is indicative of the way he approached film early on in his career--adopting and incorporating very stylized, very non-conventional kinds of cinematic techniques into his own narratives. One of the problems that a lot of people had with Do the Right Thing is that the narrative structure was very unconventional, both in terms of the way the story evolves, but perhaps more importantly, in terms of the way in which the story is concluded. That is how he goes about trying to engage in narrative closure, when in fact, he engages in a more open-ended kind of narrative structure.

We as filmgoers are so accustomed to movies where there's a definitive beginning, definitive middle and decisive end. I think that Do the Right Thing threw a lot of people off and was perhaps part of what made it a sensational movie in 1989--sensational in the sense that perhaps more so than any other movie during that year, it attracted considerable media attention. It attracted considerable attention within the academic community. There was a very interesting and profound buzz about the movie, and I think part of that was because the movie ended on a series of question marks as opposed to definitive conclusions and definitive statements. It left people wondering, "What was the right thing?" Was Mookie right or justified when he threw the trash can through Sal's pizzeria window and then started the incident that ensued from that point on? What are the right racial politics and black political ideology? Is it Malcolm's version or is it Martin Luther King Jr.'s version? What are the best and most effective ways for blacks to deal with perceived racial injustices and real racial injustices?

We as filmgoers are so accustomed to movies where there's a definitive beginning, definitive middle and decisive end. I think that Do the Right Thing threw a lot of people off and was perhaps part of what made it a sensational movie in 1989--sensational in the sense that perhaps more so than any other movie during that year, it attracted considerable media attention. It attracted considerable attention within the academic community. There was a very interesting and profound buzz about the movie, and I think part of that was because the movie ended on a series of question marks as opposed to definitive conclusions and definitive statements. It left people wondering, "What was the right thing?" Was Mookie right or justified when he threw the trash can through Sal's pizzeria window and then started the incident that ensued from that point on? What are the right racial politics and black political ideology? Is it Malcolm's version or is it Martin Luther King Jr.'s version? What are the best and most effective ways for blacks to deal with perceived racial injustices and real racial injustices?

So because the movie ended in that way, I think it caught a lot of people off guard and left a lot of people pondering a lot of different questions, which I actually liked because what it does is, unlike most films, which pretend that the kinds of issues, conflicts and crises that it might address during the middle of the film, instead of pretending that those conflicts, tensions and crises can be easily resolved through some heroic individual or some heroic stance, what Do the Right Thing suggests is that many of society's deepest and most profound social problems are in some ways almost unfortunately... very difficult, and you can't come up with a very tidy ending to address these issues. This is something that we need to leave open-ended. This is a debate that we need to have, an ongoing conversation. I think the movie, in terms of a narrative sense, provoked that kind of discourse, provoked that kind of conversation. When I was in graduate school at the time, I could remember a number of different panels and a number of different forums. Even one of the local theaters in the city where I was in school in Michigan actually screened the movie and then had a post-film discussion.

To be continued. In Part 3 of this series of excerpts from archived interviews about Do the Right Thing, Watkins praises the film's nuanced characters.

(Previously on AFOS: The Blog: Part 1. The following is from July 1, 2009.)

"I've been listening to 'Cool Jerk' by the Capitols. It's a real classic, fast and upbeat, and it brings to mind summer in the city. This may be the song for the opening credits sequence. I see Rosie Perez dancing to 'Cool Jerk' all over Brooklyn at the first heat of dawn. Rosie doing the Cool Jerk on the Brooklyn Bridge, on the promenade, and on various rooftops."

--Spike Lee, the May 17, 1988 entry in his production journal, Do the Right Thing (Fireside Books, 1989)

Do the Right Thing wouldn't have been the same without Public Enemy's rousing and confrontational original song, "Fight the Power." I can't imagine the film opening with Lee's earlier choice of "Cool Jerk." The series of excerpts from my 1999 A Fistful of Soundtracks interviews with African American Do the Right Thing experts continues with a discussion with S. Craig Watkins, a UT Austin professor of sociology, African American studies and radio-television-film, about one of the film's most powerful and effective elements, its soundtrack.

The Do the Right Thing soundtrack consisted of original songs by artists ranging from P.E. to Take 6 and a Copland-esque original jazz score composed by Lee's father Bill and performed by the Natural Spiritual Orchestra, which you can hear selections from on the Fistful of Soundtracks channel. For the film, Bill Lee assembled a septet that included saxman Branford Marsalis and trumpeter Terence Blanchard (who later became Lee's regular composer), as well as a 48-piece string section.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jimmy J. Aquino: Although Do the Right Thing was a pivotal moment in black cinema, the mainstream films directed by African Americans in the next couple of years were from the gangsta genre instead of being influenced by the Spike Lee Joints, which were more cerebral. Why was that so?

S. Craig Watkins: Much of black cinema, I would argue, tends to be influenced by what's happening in black popular music. In Do the Right Thing, you see Spike using a number of different kinds of black musical genres, styles and traditions. The one song that really, really drives the movie and I think is the most remembered is the song "Fight the Power" by Public Enemy, which is playing into this kind of hyper-racialized neo-black nationalist politics that were taking place during that time, and so he features that and uses that as the energy that drives his movie. But as that's happening, at the same time, we see in 1988/1989/1990 a new trend taking place within the field of black American popular music, more specifically rap music, in terms of the emergence of gangsta rap, and what we see eventually in the film industry, again tapping into that same energy, tapping into that same vibe, tapping into what gangsta rap was saying, doing and how it was resonating with consumers. So we see the movies also turning more and more in that direction...

JJA: Is there anything else that you find intriguing about Spike Lee's use of music in Do the Right Thing?

SCW: Yeah, one of the things I like to say in terms of giving Spike Lee some props regarding his movies is that he's always understood that black musical styles and traditions have a long history, a long legacy and are very diverse. Compare, for example, soundtracks that were typically associated with a lot of popular action ghetto-themed movies throughout the 1990s. Most of these soundtracks are most exclusively gangsta rap music, hardcore, harder-edged kind of music, which in some ways, don't necessary illuminate the complex and rich history of black music.

On the other hand, soundtracks that Spike Lee generally compiled for his movies--and Do the Right Thing is a perfect example--you've got your traditional R&B songs on there, a reggae-style joint on there, you have the rap music by Public Enemy, you have the black female rhythm and blues tradition... He did a jazz score for the movie and subsequently released a jazz score CD. So my main point is that Do the Right Thing, that soundtrack, as well as a number of his other films--particularly School Daze comes to mind--he draws from a broad cross-section of black musical traditions, tapping into an understanding, just how complex, diverse and dynamic black American music has been.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Not all the films we love are perfect. The Cambridge Film Handbooks volume on Do the Right Thing that UF Gainesville English professor Mark A. Reid edited is a compilation of essays that both praise and critique Lee's controversial film. The book also reprints film critics' reviews of Do the Right Thing from the summer of 1989. During A Fistful of Soundtracks' 1999 episode about Do the Right Thing, I wanted to hear from Reid what he thought were the film's merits and if there was anything that was missing from Lee's depiction of 1989 Bed-Stuy.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

JJA: In the film's portrayal of Bed-Stuy and the interracial tensions... is there anything in this portrayal of racial politics that it overlooks?

Mark A. Reid: Well, one would have to know the Bedford-Stuyvesant area pretty well to be able to say that it overlooks it, but I think it gives an ample picture of the different types of African Americans that live there. You have the West Indians and the different types, and you have the African Americans. You have the fact that there are Korean shopkeepers. Perhaps when Spike was younger, they weren't Korean. They were probably either Jewish or maybe Arab. The fact that there's gentrification going on in Bed-Stuy. But gentrification isn't always white yuppie. It's also buppies. We can see that in Jungle Fever, when in fact, the people who live in that area--and I think it's Harlem--the people that gentrified that area, and they're all upwardly mobile African American couples. You do have the hanger-on who's probably been there a long time... and you have different types of reactions by this Italian American family. I think that's interesting.

You don't get much of an art community around there, and I think there is a black art community that developed because they couldn't afford to live in Manhattan. You don't get the fact that there's drugs, and everybody has criticized him for that. I think if he introduced that, he'd have to develop it, and it would probably overtake the story he's trying to tell...

Do the Right Thing, although it's interesting and everything, I still think it's a very thin film. I think it's an important film because politically, how it was used when it came out and what is criticized in the film, not only Koch, but the brutality that some law officers--although that, I think, was an accident--they abuse their power. It does talk about the tension that was mounting, that would later erupt, and not only in Bedford-Stuyvesant, but in Los Angeles, the trial of Rodney King. It's like a marker. It sees certain things that are happening in the urban situation between blacks and other ethnics. Because ultimately, it did happen between the Korean businesspersons in Los Angeles.

JJA: And also, years before in New York, there were conflicts between the Korean shopkeepers and the blacks.

MAR: Right. But the thing is that what would have been interesting is that also--which is I guess it's hard to do in most films since you have a singular narrative that dominates a film--is that it's very important to understand who those Koreans are and their culture, and that's what we don't get. If Koreans come from a culture where you don't touch people when you're handing back the money or other things, and other people who aren't Korean read it differently, then there's a miscommunication, and it's on both parts, the Koreans and whoever the other community is, be it African American or Mexican American or whatever. It would be interesting to have a film that dealt with that and dealt with what Do the Right Thing did.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Watkins explains why even some black viewers thought Do the Right Thing fell short.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

SCW: I would argue that the problem with Do the Right Thing in retrospect is that it also illuminated some of the limitations with the kind of racial politics, the racial ideology, that the movie both played on and used as a driving and narrative force. Some thought that it was a bit overdone, in terms of the black racial politics. Some thought that the black racial politics were articulated in ways that weren't either nuanced or very sophisticated, in terms of the kinds of characters who were the leading proponents of a prism of the black progressive agenda. Here, I'm talking about, for example, the character of Buggin' Out, who many argue--and I think accurately so--was basically more of a caricature than a character per se.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

I asked Reid about some black viewers' gripes with Giancarlo Esposito's Buggin' Out character.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

JJA: There's this interesting criticism about Buggin' Out, that Spike Lee's portrayal of Buggin' Out is a mockery of black political activism.

MAR: It's a mockery in a sense that what Buggin' Out wants to do is boycott Sal's, as opposed to... In the history of African Americans, we boycott, and we also choose another alternative to Sal at the same time. What Buggin' Out wants to do is change pictures, which really doesn't mean that much. It's superficial.

JJA: It's about image.

MAR: Right. Why wouldn't he say, "Hire more people from the community"? Why wouldn't he help support somebody else who wants to build a small restaurant and teach them--an internship? That's what a boycott could do. A boycott to change photographs on a wall? "You put up Muhammad Ali and you put up a basketball player"? So what? That's decoration.

But even within the film, the characters didn't take Buggin' Out that seriously. Spike Lee using those characters and taking that not so seriously means that they're waiting for a more serious type of political activism than what Buggin' Out offers them. So I wouldn't look at it totally as a critique of black activism. I'd look at it as a critique of a certain type of black activism, which might, in fact, be a critique of Al Sharpton. That hasn't ever been discussed, but you could see that at that point in time. I don't know what "Tawana Told the Truth" means. Are we supposed to take it seriously or is it like a critique of the Tawana Brawley thing? That's the problem too... But the thing is that do we want a conclusive "Yes, this is what it's about"? Or do we want to be forced to think about these issues? I think that maybe that's what Spike Lee is doing.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Watkins offers his take on the film's open-endedness.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

JJA: Another intriguing aspect about Do the Right Thing is the narrative techniques. What's unconventional about these narrative techniques?

SCW: What Spike does in Do the Right Thing in some ways is indicative of the way he approached film early on in his career--adopting and incorporating very stylized, very non-conventional kinds of cinematic techniques into his own narratives. One of the problems that a lot of people had with Do the Right Thing is that the narrative structure was very unconventional, both in terms of the way the story evolves, but perhaps more importantly, in terms of the way in which the story is concluded. That is how he goes about trying to engage in narrative closure, when in fact, he engages in a more open-ended kind of narrative structure.

We as filmgoers are so accustomed to movies where there's a definitive beginning, definitive middle and decisive end. I think that Do the Right Thing threw a lot of people off and was perhaps part of what made it a sensational movie in 1989--sensational in the sense that perhaps more so than any other movie during that year, it attracted considerable media attention. It attracted considerable attention within the academic community. There was a very interesting and profound buzz about the movie, and I think part of that was because the movie ended on a series of question marks as opposed to definitive conclusions and definitive statements. It left people wondering, "What was the right thing?" Was Mookie right or justified when he threw the trash can through Sal's pizzeria window and then started the incident that ensued from that point on? What are the right racial politics and black political ideology? Is it Malcolm's version or is it Martin Luther King Jr.'s version? What are the best and most effective ways for blacks to deal with perceived racial injustices and real racial injustices?

We as filmgoers are so accustomed to movies where there's a definitive beginning, definitive middle and decisive end. I think that Do the Right Thing threw a lot of people off and was perhaps part of what made it a sensational movie in 1989--sensational in the sense that perhaps more so than any other movie during that year, it attracted considerable media attention. It attracted considerable attention within the academic community. There was a very interesting and profound buzz about the movie, and I think part of that was because the movie ended on a series of question marks as opposed to definitive conclusions and definitive statements. It left people wondering, "What was the right thing?" Was Mookie right or justified when he threw the trash can through Sal's pizzeria window and then started the incident that ensued from that point on? What are the right racial politics and black political ideology? Is it Malcolm's version or is it Martin Luther King Jr.'s version? What are the best and most effective ways for blacks to deal with perceived racial injustices and real racial injustices? So because the movie ended in that way, I think it caught a lot of people off guard and left a lot of people pondering a lot of different questions, which I actually liked because what it does is, unlike most films, which pretend that the kinds of issues, conflicts and crises that it might address during the middle of the film, instead of pretending that those conflicts, tensions and crises can be easily resolved through some heroic individual or some heroic stance, what Do the Right Thing suggests is that many of society's deepest and most profound social problems are in some ways almost unfortunately... very difficult, and you can't come up with a very tidy ending to address these issues. This is something that we need to leave open-ended. This is a debate that we need to have, an ongoing conversation. I think the movie, in terms of a narrative sense, provoked that kind of discourse, provoked that kind of conversation. When I was in graduate school at the time, I could remember a number of different panels and a number of different forums. Even one of the local theaters in the city where I was in school in Michigan actually screened the movie and then had a post-film discussion.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

To be continued. In Part 3 of this series of excerpts from archived interviews about Do the Right Thing, Watkins praises the film's nuanced characters.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)