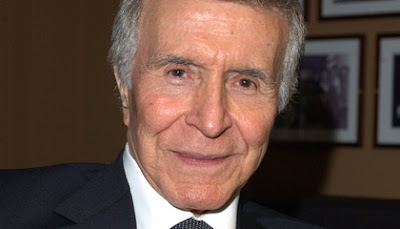

As I found out about Montalban's death, TCM happened to be airing the MGM: When the Lion Roars documentary, which features the former MGM contract player and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan star as an interviewee. The lengthy doc traces the rise and fall of "the Tiffany studio," and Montalban, in his smooth Latin playah voice, laments how "the lion stopped roaring."

Montalban was one of the few remaining survivors of the era of the studio system--a system that both helped and hurt his career. In an interesting 2002 Palm Beach Post article that unfortunately is no longer online, Montalban, who at the time was promoting TCM's Hispanic Heritage Month tribute to Hispanics in cinema, recalled his days as one of Hollywood's few Latino movie stars:

Montalban, a star in his native Mexico -- his parents were Castilian Spanish, but his physician father moved the family to Mexico before he was born -- had his troubles in Hollywood. When he was signed by MGM in 1946, there was a movement afoot to change his name to -- wait for it -- Ricky Martin.Because of the lack of substantial big-screen roles for Latinos and the decline of the studio system, Montalban made the jump to TV. But the small screen wasn't much of an improvement for Latinos (and everyone else who was a minority), because Montalban guest-starred as a '90s dictator from India (Khan Noonien Singh on Star Trek), a Frenchman (Combat!) and a Japanese gangster (Hawaii Five-0) and then ruled the '70s and '80s Saturday night airwaves as a mysterious island resort owner of indeterminate race (Fantasy Island).

"They couldn't pronounce my name," he says today. "Joe Pasternak, the producer, would introduce me to people as Richard Mandelbaum. Eight times out of 10, I was Richard Mandelbaum, but a couple of times I was Richard Mountbatten, and at least once he said Richard Musclebound. He had a hell of a time with it.

"So they thought my name was impossible, and they were going to change it, but then they consulted with the man who was in charge of the Latin America market, and he said, 'He has a following here, you can't change his name.' And that's the only reason I managed to retain my dignity."

The studios' strengths were in stereotyping -- the blond bombshell, the ultra-masculine leading man, etc. -- so the Hispanics they had under contract were no exception.

"I approached directors, producers, executives and tried to convince them to create other characters besides the Mexican bandit and the hot senorita. Call it ignorance, but they would tell me, 'We're trying to put as many colorful characters in the movies as we can.' They called these stereotypes 'colorful.' "

Not only that, but Montalban was aware of an even subtler prejudice. Montalban played Cubans, played Argentinians, played Brazilians, but it took years before he could play a Mexican.

"Mexico didn't sound quite right, even though we have the best muralists in the world, some of the best painters, the best heart specialists. Where were they on the screen, people of dignity, wealth and culture? Or even the very honorable middle-class man who struggles to give his kids a better education. 'An architect is not colorful,' they would tell me."

MGM didn't stint on Montalban; he worked opposite the studio's top leading ladies, from Lana Turner to Jane Powell, and was given several films in the early '50s as a stand-alone lead, though he points out that they were B films.

Even when Montalban resented the roles he was assigned, his options were limited. "When I would say, I don't want to do it, it's vapid, they would say, 'All right, you don't have to do it. But we'll put you on suspension for six months.' So that vapid role became a great role. I had a wife and four children; I never went on suspension because I couldn't afford it."

There was no cohesion within the Hispanic community in Hollywood -- everybody worked at different studios, and went home to their different houses. That would eventually lead Montalban to found Nosotros, an organization to promote Hispanic talent so that, as he puts it, "we could be judged on our ability or lack of ability, not by our names."

Whether the role was inane (the taped-eyelidded act on Five-0) or not (Khaaaaaaaaaan!), Montalban the serial guest star--and serial Fakeasian--brought to each of his live-action or animated performances a certain regal movie-star charisma that boosted the show. That same charisma helped add an edge to Wrath of Khan that was missing from the first Trek feature film. Returning to a character he played 15 years earlier, Montalban was pitch-perfect as the genetically engineered titular villain, or as Robin Harris would have called him, "Test-tube baby!"

Montalban also played equally pivotal roles in the Planet of the Apes and Spy Kids franchises. Speaking of spies...

Another great actor has died: Patrick McGoohan, star and co-creator of both Danger Man, a.k.a. Secret Agent, and its unofficial sequel The Prisoner, which he memorably parodied on The Simpsons in one of his last bits of acting.

The Danger Man creators used the Bond novels as a springboard to conceive a spy hero who was different from Ian Fleming's "blunt instrument." John Drake wasn't much of a skirtchaser and was less violent and glamorous than 007. McGoohan actually turned down the film version of Dr. No because the actor, a devout Catholic, wasn't comfortable with playing a womanizer. But he had no objections to playing the cerebral Drake, the antithesis of Bond.

Like Montalban, McGoohan excelled in villainous roles, from Silver Streak to Columbo. He played four different killers on both the NBC and ABC versions of the Peter Falk TV-movie franchise and won Emmys for two of those characters. By Dawn's Early Light is my favorite Columbo installment because McGoohan is so mesmerizing as an unflappable military school commandant.

Wired's Underwire blog has posted a detailed remembrance of McGoohan, who wanted individuality in everything he did. "It's not easy to find it always," he said as he channeled Number Six from The Prisoner. "I question everything. I don't accept anything on face value."

Here's the classic Prisoner opening title sequence, scored by Ron Grainer, who also composed the Doctor Who theme, and featuring guitar work by Vic Flick, who performed the guitar riffs during the Dr. No version of "The James Bond Theme":

No comments:

Post a Comment