"Williams brings on the movie's signature piece, the 'March from 1941,' which will inform and underlie almost everything that comes after it. The march, instantly hummable, melds the fighting spirit of everything from Kenneth Alford and Malcolm Arnold's 'Colonel Bogey March' (The Bridge on the River Kwai), to the playful exuberance and bombast of Elmer Bernstein's The Great Escape, to the echoes of lost national spirit that tumble through Jerry Goldsmith's rousing score for Patton. Yet Williams is never caught cribbing lines or themes--the genius of the music is that is [sic] finds its own spirit, equivalent to the cacophonous madness of the film, yet also coursing with a generous and goofy charm and sense of its own scale that makes a listener laugh even without the attendant imagery."

--from film blogger Dennis Cozzalio's 2010 post about John Williams' 1941 score

Unless it's a Chris Rock routine, a Lewis Black rant, a Will Ferrell girlie-crying jag or Nicolas Cage screaming "Oh no! Not the bees!! Not the bees!! Aaaaaaaaahhhhhhhh!!! Oh! They're in my eyes!! My eyes!!," yelling is such a comedy killer for me. If you like your comedy broad and always shouty, the expensive 1979 WWII farce 1941, Steven Spielberg's first--and not surprisingly, only--attempt at directing a straight-up comedy, is up your alley. But for the rest of us, 1941 can be a chore to watch as it tries too hard to be funny and assumes nonstop loudness--even the end credits curtain call consists of clips of cast members yelling--will automatically yield laughs. No wonder the few funny or amusing moments in Spielberg's John Carter-style financial failure are, of course, moments where no one's yelling.

The whole story of getting 1941 made may be more fascinating than the film itself. 1941 producer and right-wing nutjob John Milius wanted to call his film The Night the Japs Attacked. We have then-MGM production chief Dan Melnick to thank for objecting to the use of "Japs" in the project's early title (back when it was attached to MGM and was nothing more than a Robert Zemeckis/Bob Gale screenplay that was darker-humored and smaller-scale than the finished product). 1941 is an example of a movie where I wish I were a fly on the wall--or better yet, an extra or crew member or whoever was put in charge of the craft services table--because I would have been surrounded by comedy icons like John Belushi, his SNL pal and Blues Brothers bandmate Dan Aykroyd, John Candy and Joe Flaherty; legendary actors like Toshiro Mifune, Christopher Lee and Warren Oates; and '70s hotties like Nancy Allen and that girl from Eight Is Enough. It's the ultimate "film that must have been more fun to make than sit through."

|

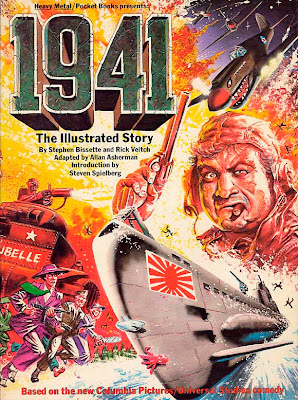

| In 1979, 1941 famously tanked. So did the little-known graphic novel tie-in. (Photo source: Steve Bissette) |

"Belushi and Aykroyd... turned the set into one big playground where they could wildly drive around in their own vintage New York taxicab and throw out random scene ideas that Spielberg gladly accepted," noted the Vulture list. "First assistant director Jerry Ziesmer's memoir, Ready When You Are, Mr. Coppola, Mr. Spielberg, Mr. Crowe, paints a portrait of an out-of-control set where everybody was constantly cracking each other up."

Actually, I come not to bury 1941 (because so many have attacked it so well already, and I'm having a hard time trying to restrain myself from constantly dissing it), but to praise its few highlights. Let's list them now: the skillfully shot USO dance number/fight sequence (it hints at what 1941 would have been like as a musical, which, at one point during production, was what Spielberg wanted to turn 1941 into, and it also proves that the film would have been better off focusing mostly on the teenage characters); the offbeat sight of Robert Stack crying over Dumbo; the wonderful pre-CGI visual effects for the ferris wheel set piece; and the most memorable highlight, John Williams' terrific score.

So I don't find 1941 to be as hilarious as fans of Spielberg's original and longer cut like Dennis Cozzalio do, but I do agree with Cozzalio about Williams' "March from 1941." A great piece of symphonic anarchy, the theme is as loud as the movie's brand of property damage-reliant humor, but aren't all national anthems supposed to be performed loudly? The 1941 march is like the national anthem of Notreadyforprimetimeplayalistica or some country in an alternate reality where comedy nerds run Congress, the Supreme Court justices are stand-ups like Dom Irrera (who's had plenty of judicial experience presiding over Audience Network's Supreme Court of Comedy) and Paul Mooney (too bad he's not a Supreme Court justice because I would love to see Mooney verbally rip apart the conservative justices over matters like President Obama's health care law) and flags were flown at half-mast when Belushi, his '70s SNL colleague Gilda Radner and '80s and '90s SNL regular Phil Hartman died.

Like yesterday's penultimate "March Madness March of the Day," Bear McCreary's Human Target theme, the 1941 march captures the spirit of other classic themes without regurgitating their melodies. It's outlasted the movie it originated from.

All the other "March Madness March of the Day" posts from this week:

"Theme from Human Target" by Bear McCreary

"Main Title" from Star Trek: The Motion Picture by Jerry Goldsmith

"Main Title" from Spartacus by Alex North

"Captain America March" from Captain America: The First Avenger by Alan Silvestri

This is the final "March Madness March of the Day" post.