Throwback Thursday is a forum for discussing past or present films we've paid to see, whether they contain score music that's currently in rotation on AFOS or don't, but it's a forum not just for myself. Hardeep Aujla--my homie from the U.K.-based international hip-hop site Word Is Bond, as well as an Asian action cinema devotee who introduced me to the batshit brilliance of The Man from Nowhere, while I hipped him to my favorite Johnnie To films--is someone whose writing we'll be seeing a lot of in this space later this year. He didn't see the 2014 thriller The Signal in the theater--where all previous Throwback Thursday subjects were watched, as shown by a movie ticket photo that usually opens each post--but he has a lot to say about this low-budget thriller he caught online. It features a nifty original score by both Nima Fakhrara, who scored the 2013 live-action version of Gatchaman, and, towards the end of the film, instrumental hip-hop artist Chris Alfaro, who records under the name Free the Robots. This is Hardeep's first Throwback Thursday piece. No British punctuation styles were harmed during the posting of this piece.

Spoilers for The Signal begin in 41... 5... 3... 2...

The Signal (2014)

By Hardeep Aujla

Once upon a rainy Switzerland weekend, Lord Byron threw a party. Probably something like Puffy would do in our times: lots of famous people in attendance. Mary Shelley was there, had a nightmare after a night of horror-story-hot-potato and penned Frankenstein for the remainder of her stay. Nearly 200 years pass and we cite it as the first piece of science-fiction. Its philosophical discourse on man's folly of playing God by creating "artificial" life would inspire artists for generations and provide the genre with one of its most endearing pre-occupations. Technology advances and the stories keep up, or sometimes already had the lead. We get a broad spectrum of mechano-stuff from the "housewives' dream" Robby The Robot, to Sarah Connor's worst nightmare, the Terminator. Isaac Asimov lays down some fundamental, human-protecting laws, anticipating an emergent property which begins to rouse between the circuit boards and soldered wires. Johnny Five says he "is alive", Pris quotes Descartes, "I think, Sebastian... therefore I am", echoing an automaton that's been sitting in the town hall at Neuchatel since the 1700's writing that exact same phrase over and over again. Today, angst around AI research is manifested in cinema with a noticeable surge in recent years. Her (2013), Chappie (2015) and Ex Machina (2015) (which I've not seen but looks to be pretty similar to 2013's The Machine, right down to the fembot's name of Ava) all compute the dilemma of nuts and bolts and code gaining sentience. Then Automata (2014) straight passes forward the baton of life to them, because how else are we gonna survive the interstellar getaway with our squishy, frail and generally not-space-friendly bodies when we eventually wreck this rock?

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Monday, April 27, 2015

"Far East style with the spirit of Wild West": Familiarize yourself with the music of Samurai Champloo co-composer Nujabes

Like I've said before, I love it when the worlds of film or TV score music and hip-hop collide. One of my favorite of those collisions is the work of the late Japanese producer Nujabes (pronounced "noo-jah-bess") as a co-composer for Shinichiro Watanabe's classic 2004-05 animated show Samurai Champloo, an intentionally anachronistic period piece full of samurai who display breakdancing fighting styles and Edo-period Japanese youth who are fond of either beatboxing or creating graffiti art.

Just like J Dilla, another beloved and distinctive producer whose death in the late '00s is still being mourned by many in the hip-hop community, Jun Seba (Nujabes is an anagram of his name), the virtuoso beatmaker and founder of his own indie label Hydeout Productions, has gained more fans posthumously than before his death from a car accident in 2009, mostly due to Samurai Champloo. Nujabes' instrumentals were pitch-perfect for Champloo (by the way, "champloo," if you've ever wondered, is the Westernized spelling of "chanpuru," a word that means "something mixed" and is also the name of an Okinawan stir-fry dish that mixes tofu with meat and bitter melon or other ingredients). The music by Nujabes, Fat Jon, Tsutchie and Force of Nature (the duo of DJ Kent and KZA) alternated between playful and contemplative, like the show itself, which alternated between raucous action comedy and the existential drama that was found in the tortured pasts of its three principal characters: unemployed rival swordsmen Mugen and Jin and their teenage charge Fuu, a mismatched trio in the mold of Watanabe's Cowboy Bebop trio of Spike, Jet and Faye.

(The cues during FUNimation's clip from "Tempestuous Temperaments," Champloo's first episode, are "Loading Zone" and "Silver Children," both by Force of Nature.)

"Plangent piano lines dominated, sometimes ornamented by flute or soprano saxophone, with a mood that hovered between melancholy and uplifting without ever tipping over into schmaltz," wrote James Hadfield about the Nujabes sound in his recent Japan Times piece about both Nujabes and frequent collaborators like Japanese rapper Shing02, whose bars grace Champloo's Nujabes-produced opening title theme "Battlecry" ("Some fight, some bleed/Sunup to sundown/The sons of a battlecry"). My favorite part of the Japan Times piece on Nujabes has to be the vivid glimpse into Nujabes' time as a persnickety, Rob Gordon-esque record shop owner in '90s Shibuya: "Sometimes the owner's personal tastes trumped commercial considerations: When Jay-Z released crossover hit 'Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)' in 1998, Seba only stocked a few copies because he didn't like the song."

Nujabes' schmaltz-free and Annie-free contributions to Champloo can be heard during the AFOS blocks "Beat Box," "Brokedown Merry Go-Round" and "AFOS Prime," as well as during a terrifically assembled mix of Nujabes instrumentals by L.A.'s Daddy Kev, which he dropped in honor of Nujabes, on the fifth anniversary of his death on February 26. The new mix contains the Champloo instrumentals "A Space in Air" (starting at 0:00), "Haiku" (at 7:51), "The Space Between Two World" (at 13:58), "Aruarian Dance" (at 21:18 and my personal all-time favorite Nujabes beat) and "Mystline" (at 50:32).

Champloo's entire run can be streamed on either FUNimation, its YouTube channel or Netflix, where you can glimpse how the music of Nujabes, Fat Jon, Tsutchie and Force of Nature is so integral to Champloo that it's like a fourth character on the show (a 2012 essay on Champloo by the hip-hop site The Find notes that the rise in Nujabes' international popularity is "partially because of careless teenagers on YouTube incorrectly crediting him with just about every track on the show, while the most often featured musician on the show and most responsible for the overall musical texture, Tsutchie, would end up criminally ignored"). But if you've never watched Champloo and you're unfamiliar with Nujabes' music, Daddy Kev's "Beyond" tribute mix is an ideal introduction to his music.

My first encounter with the Nujabes sound was a bizarre one: it wasn't through Champloo but through a remix of Amerie's "1 Thing," which made the rounds of the blogosphere back in 2005 for brilliantly mashing up "1 Thing" with Nujabes. The remix was the work of an L.A. remixer and DJ named Siik, whose bizarrely named mixes are among my favorites. Siik's "I Don't Even Like Coffee" receives frequent MacBook airplay from me, simply for the inclusion of the underrated, Dilla-produced A Tribe Called Quest track "Like It Like That."

It wasn't until nearly a decade after the "1 Thing" remix--while watching all of Champloo for the first time, in subtitled form and online, and then becoming such a Nujabes fan that my older brother got me a Hydeout compilation last Christmas--when I realized the instrumental Siik chose for his "1 Thing" remix, "Aruarian Dance," came from Champloo. That made me like Siik's remix even more. And now, since it's such a great sampler of Nujabes instrumentals, Daddy Kev's "Beyond" tribute mix joins the likes of the "1 Thing" remix and "I Don't Even Like Coffee" as something I'll frequently vibe to on my MacBook, sunup to sundown.

Just like J Dilla, another beloved and distinctive producer whose death in the late '00s is still being mourned by many in the hip-hop community, Jun Seba (Nujabes is an anagram of his name), the virtuoso beatmaker and founder of his own indie label Hydeout Productions, has gained more fans posthumously than before his death from a car accident in 2009, mostly due to Samurai Champloo. Nujabes' instrumentals were pitch-perfect for Champloo (by the way, "champloo," if you've ever wondered, is the Westernized spelling of "chanpuru," a word that means "something mixed" and is also the name of an Okinawan stir-fry dish that mixes tofu with meat and bitter melon or other ingredients). The music by Nujabes, Fat Jon, Tsutchie and Force of Nature (the duo of DJ Kent and KZA) alternated between playful and contemplative, like the show itself, which alternated between raucous action comedy and the existential drama that was found in the tortured pasts of its three principal characters: unemployed rival swordsmen Mugen and Jin and their teenage charge Fuu, a mismatched trio in the mold of Watanabe's Cowboy Bebop trio of Spike, Jet and Faye.

(The cues during FUNimation's clip from "Tempestuous Temperaments," Champloo's first episode, are "Loading Zone" and "Silver Children," both by Force of Nature.)

"Plangent piano lines dominated, sometimes ornamented by flute or soprano saxophone, with a mood that hovered between melancholy and uplifting without ever tipping over into schmaltz," wrote James Hadfield about the Nujabes sound in his recent Japan Times piece about both Nujabes and frequent collaborators like Japanese rapper Shing02, whose bars grace Champloo's Nujabes-produced opening title theme "Battlecry" ("Some fight, some bleed/Sunup to sundown/The sons of a battlecry"). My favorite part of the Japan Times piece on Nujabes has to be the vivid glimpse into Nujabes' time as a persnickety, Rob Gordon-esque record shop owner in '90s Shibuya: "Sometimes the owner's personal tastes trumped commercial considerations: When Jay-Z released crossover hit 'Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)' in 1998, Seba only stocked a few copies because he didn't like the song."

Nujabes' schmaltz-free and Annie-free contributions to Champloo can be heard during the AFOS blocks "Beat Box," "Brokedown Merry Go-Round" and "AFOS Prime," as well as during a terrifically assembled mix of Nujabes instrumentals by L.A.'s Daddy Kev, which he dropped in honor of Nujabes, on the fifth anniversary of his death on February 26. The new mix contains the Champloo instrumentals "A Space in Air" (starting at 0:00), "Haiku" (at 7:51), "The Space Between Two World" (at 13:58), "Aruarian Dance" (at 21:18 and my personal all-time favorite Nujabes beat) and "Mystline" (at 50:32).

Champloo's entire run can be streamed on either FUNimation, its YouTube channel or Netflix, where you can glimpse how the music of Nujabes, Fat Jon, Tsutchie and Force of Nature is so integral to Champloo that it's like a fourth character on the show (a 2012 essay on Champloo by the hip-hop site The Find notes that the rise in Nujabes' international popularity is "partially because of careless teenagers on YouTube incorrectly crediting him with just about every track on the show, while the most often featured musician on the show and most responsible for the overall musical texture, Tsutchie, would end up criminally ignored"). But if you've never watched Champloo and you're unfamiliar with Nujabes' music, Daddy Kev's "Beyond" tribute mix is an ideal introduction to his music.

My first encounter with the Nujabes sound was a bizarre one: it wasn't through Champloo but through a remix of Amerie's "1 Thing," which made the rounds of the blogosphere back in 2005 for brilliantly mashing up "1 Thing" with Nujabes. The remix was the work of an L.A. remixer and DJ named Siik, whose bizarrely named mixes are among my favorites. Siik's "I Don't Even Like Coffee" receives frequent MacBook airplay from me, simply for the inclusion of the underrated, Dilla-produced A Tribe Called Quest track "Like It Like That."

It wasn't until nearly a decade after the "1 Thing" remix--while watching all of Champloo for the first time, in subtitled form and online, and then becoming such a Nujabes fan that my older brother got me a Hydeout compilation last Christmas--when I realized the instrumental Siik chose for his "1 Thing" remix, "Aruarian Dance," came from Champloo. That made me like Siik's remix even more. And now, since it's such a great sampler of Nujabes instrumentals, Daddy Kev's "Beyond" tribute mix joins the likes of the "1 Thing" remix and "I Don't Even Like Coffee" as something I'll frequently vibe to on my MacBook, sunup to sundown.

Thursday, April 23, 2015

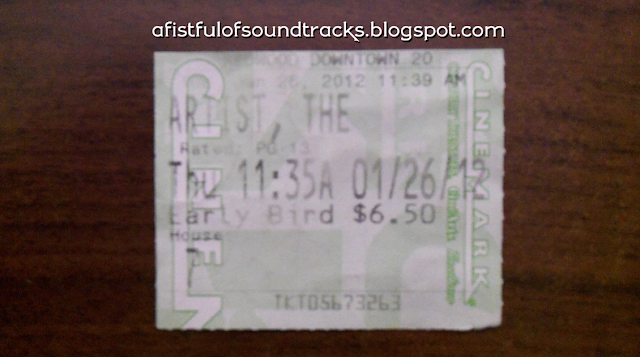

Throwback Thursday: The Artist

Every Throwback Thursday, I randomly pull out from my desk cabinet--with my eyes closed--a movie ticket I saved. Then I discuss the movie on the ticket and maybe a little bit of its score, which might be now streaming on AFOS.

French director Michel Hazanavicius' 2011 silent movie The Artist, the 2012 Best Picture Oscar winner about the end of the silent era in Hollywood, is impossible to dislike. It reteams Jean Dujardin with Hazanavicius' wife Bérénice Bejo--who starred together in OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies, Hazanavicius' amusing 2006 spy spoof about a racist and misogynist '50s French agent--and demonstrates how perfectly cast the two expressive and subtle French stars are as fictional late '20s Hollywood actors who exemplify certain emotive and non-verbal acting styles that were prevalent during The Artist's time period.

In addition to those star turns by Dujardin, who won an Oscar for his role, and the luminous Bejo, a smart and heroic Jack Russell terrier--played by three different dogs--often entertainingly steals the show (the Artist DVD's outtakes of the canine actors missing their cues or ignoring their trainer's instructions are equally entertaining, proving Robert Smigel's theory that much of the funniness of animal actors is due to them not having "any idea what they're part of"). James Cromwell brings his usual material-boosting gravitas to a role that's non-villainous for a change, a stoic and loyal chauffeur who enjoys his work, while, like Dujardin and Bejo, the frequently funny Missi Pyle was born to act in a silent movie, as we see in a way-too-brief role that's clearly an homage to Lina Lamont, Jean Hagen's villainous silent movie star character from Singin' in the Rain.

Another plus is Hazanavicius' attention to the details of late '20s/early '30s Hollywood, with some assistance from his regular composer Ludovic Bource. His Oscar-winning Artist score was influenced by the studio-system-era likes of Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann, whose classic "Scene d'Amour" cue from Vertigo was needle-dropped at one point in The Artist by Hazanavicius, a Hitchcock fan. But the inclusion of a score cue from a well-known 1958 Hitchcock picture during a movie that takes place way before 1958 was too much of an off-putting distraction for some moviegoers, especially Vertigo star Kim Novak, whose bizarre public statement where she angrily referred to the needle drop as "rape" led to a hilarious reaction from Kumail Nanjiani.

It's not as if Hazanavicius soundtracked the movie's angsty climax with Evanescence's "Bring Me to Life," but the purists in the audience who were bent out of shape about the climax would rant and rave as if the director Evanescenced it. Whether or not anachronistic music choices in The Artist or other period pieces like Inglourious Basterds and Public Enemies set off your inner Pierre Bernard, you can't deny how The Artist remarkably never looks like it was made in 2010, thanks mostly to the striking black-and-white visuals of Hazanavicius' regular cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman. At one point, the movie, which Hazanavicius shot entirely in Hollywood, makes beautiful use of the distinctive staircase inside the Bradbury Building, the 122-year-old L.A. filming location most memorably featured in Blade Runner and the 1964 Outer Limits episode "Demon with a Glass Hand."

So like I said before, The Artist is impossible to dislike. But it's hardly the best picture of 2011. As silent movies that were made long after the silent era, Mel Brooks' 1976 farce Silent Movie and Charles Lane's 1989 indie flick Sidewalk Stories are more inventive than The Artist, which, while it does recapture '20s and '30s filmmaking quite well, never really does anything inventive or new with the silent gimmick, other than a memorable nightmare sequence where Dujardin's George Valentin imagines the horrors of being trapped in a new world full of sound. The scenes where George drinks himself into a stupor--over his artistic decline and his inability to adapt to Hollywood's transition from silents to talkies like the box-office successes of Bejo's Peppy Miller--really drag. George's self-pity is about 10 minutes too long. It becomes so repetitive that an enticing-looking two-second clip of Peppy from a fake movie where she stars as a female baseball player ends up being a movie I'd rather watch instead of the actual movie surrounding it.

French director Michel Hazanavicius' 2011 silent movie The Artist, the 2012 Best Picture Oscar winner about the end of the silent era in Hollywood, is impossible to dislike. It reteams Jean Dujardin with Hazanavicius' wife Bérénice Bejo--who starred together in OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies, Hazanavicius' amusing 2006 spy spoof about a racist and misogynist '50s French agent--and demonstrates how perfectly cast the two expressive and subtle French stars are as fictional late '20s Hollywood actors who exemplify certain emotive and non-verbal acting styles that were prevalent during The Artist's time period.

In addition to those star turns by Dujardin, who won an Oscar for his role, and the luminous Bejo, a smart and heroic Jack Russell terrier--played by three different dogs--often entertainingly steals the show (the Artist DVD's outtakes of the canine actors missing their cues or ignoring their trainer's instructions are equally entertaining, proving Robert Smigel's theory that much of the funniness of animal actors is due to them not having "any idea what they're part of"). James Cromwell brings his usual material-boosting gravitas to a role that's non-villainous for a change, a stoic and loyal chauffeur who enjoys his work, while, like Dujardin and Bejo, the frequently funny Missi Pyle was born to act in a silent movie, as we see in a way-too-brief role that's clearly an homage to Lina Lamont, Jean Hagen's villainous silent movie star character from Singin' in the Rain.

Another plus is Hazanavicius' attention to the details of late '20s/early '30s Hollywood, with some assistance from his regular composer Ludovic Bource. His Oscar-winning Artist score was influenced by the studio-system-era likes of Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann, whose classic "Scene d'Amour" cue from Vertigo was needle-dropped at one point in The Artist by Hazanavicius, a Hitchcock fan. But the inclusion of a score cue from a well-known 1958 Hitchcock picture during a movie that takes place way before 1958 was too much of an off-putting distraction for some moviegoers, especially Vertigo star Kim Novak, whose bizarre public statement where she angrily referred to the needle drop as "rape" led to a hilarious reaction from Kumail Nanjiani.

Hey Kim Novak, did you know that only 10% of iconic soundtrack theft is actually reported?

— Kumail Nanjiani (@kumailn) January 9, 2012

Guessing Kim Novak's never been raped.

— Kumail Nanjiani (@kumailn) January 9, 2012

It's not as if Hazanavicius soundtracked the movie's angsty climax with Evanescence's "Bring Me to Life," but the purists in the audience who were bent out of shape about the climax would rant and rave as if the director Evanescenced it. Whether or not anachronistic music choices in The Artist or other period pieces like Inglourious Basterds and Public Enemies set off your inner Pierre Bernard, you can't deny how The Artist remarkably never looks like it was made in 2010, thanks mostly to the striking black-and-white visuals of Hazanavicius' regular cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman. At one point, the movie, which Hazanavicius shot entirely in Hollywood, makes beautiful use of the distinctive staircase inside the Bradbury Building, the 122-year-old L.A. filming location most memorably featured in Blade Runner and the 1964 Outer Limits episode "Demon with a Glass Hand."

So like I said before, The Artist is impossible to dislike. But it's hardly the best picture of 2011. As silent movies that were made long after the silent era, Mel Brooks' 1976 farce Silent Movie and Charles Lane's 1989 indie flick Sidewalk Stories are more inventive than The Artist, which, while it does recapture '20s and '30s filmmaking quite well, never really does anything inventive or new with the silent gimmick, other than a memorable nightmare sequence where Dujardin's George Valentin imagines the horrors of being trapped in a new world full of sound. The scenes where George drinks himself into a stupor--over his artistic decline and his inability to adapt to Hollywood's transition from silents to talkies like the box-office successes of Bejo's Peppy Miller--really drag. George's self-pity is about 10 minutes too long. It becomes so repetitive that an enticing-looking two-second clip of Peppy from a fake movie where she stars as a female baseball player ends up being a movie I'd rather watch instead of the actual movie surrounding it.

Monday, April 20, 2015

When enjoyable scores are attached to terrible movies, or why I feel kind of awful about adding Wild Wild West score music to "AFOS Incognito" rotation

I don't care for Madonna and her cultural-appropriating ass, but I've always liked the music of William Orbit. The Drake-scaring pop star's hit single from the summer of 1999, "Beautiful Stranger," a '60s-pop-flavored tune she recorded for Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, is my favorite pop song Orbit has produced because it's Orbit at his most playful-sounding, from the Ron Burgundy flute funk to the harpsichord riffs (the harpsichord is also integral to why my favorite Michael Jackson tune is "I Wanna Be Where You Are"). "Beautiful Stranger" is featured in The Spy Who Shagged Me for like only 30 seconds, during a non-comedic scene where the titular '60s spy mourns the loss of his mojo. Because of "Beautiful Stranger," I would have been interested in what Madonna and Orbit would have recorded together for Guy Ritchie's upcoming remake of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., had Ritchie and Madonna never split.

"Beautiful Stranger" is pitch-perfect for the breezy, psychedelic, Laugh-In-esque and Derek Flint-inspired Austin Powers franchise, whereas Madonna's other original spy movie theme, the Mirwais-produced electroclash tune "Die Another Day," doesn't quite work for 007 (it would have worked for some other spy franchise: maybe Totally Spies?). The Die Another Day theme makes you wonder if Madonna or Mirwais ever even watched an actual 007 movie beforehand, even though she claimed that the Die Another Day screenplay influenced the lyrics she wrote (the orchestral string riffs during "Die Another Day" came not from Die Another Day score composer David Arnold but from Madonna's "Don't Tell Me" collaborator, the late New Jack City score composer Michel Colombier, and I would have enjoyed Colombier's string riffs a little more if they had at least some ounce of thematic connection to anything Arnold wrote for his score).

I fell in love with "Beautiful Stranger" again a few weeks ago while overhearing it being played on some store PA during a round of book-shopping or grocery-shopping (I can't remember which kind of shopping it was). So that's why I'm adding "Beautiful Stranger" to the playlist for the espionage genre music block "AFOS Incognito," where it can be enjoyed without having to be subjected to any visuals directed by Brett Ratner, Mondays through Thursdays at midnight Pacific on AFOS.

There's one other piece of music from a 1999 spy comedy that I'm adding to "AFOS Incognito," and this spy comedy isn't exactly as beloved as The Spy Who Shagged Me was back in 1999. It's from the second and final film in Warner Bros.' late '90s mission to ruin your favorite TV shows, Wild Wild West, the Will Smith/Kevin Kline blockbuster loosely based on the '60s spy show/proto-steampunk western of nearly the same name (the show was called The Wild Wild West, while the movie omitted "The" from the title).

Fortunately, the selected piece of music isn't the ubiquitous-on-the-1999-airwaves Will Smith/Dru Hill theme tune that was never worthy of sampling Stevie Wonder's "I Wish." It's the other memorable piece of music from Wild Wild West: the rousing main title theme by a legendary composer who wrote a million rousing themes for westerns, the late Magnificent Seven score composer Elmer Bernstein. That Bernstein main title theme is the only thing I like about Wild Wild West. IMDb is wrong: it's not "a generic piece of music." It's classic Bernstein western music, faithful in spirit to Richard Markowitz's equally rousing '60s Wild Wild West theme tune, which either the filmmakers couldn't get the full rights to or were too dunderheaded to use more often in the film because of their hubris and contempt for the source material (although I wouldn't consider The Wild Wild West a perfect show: it suffers from that old '60s and '70s spy show staple of stupidly putting white actors in yellowface or brownface). The theme is too good for such a hackily written steaming pile and such a chemistry-deficient buddy action flick.

Speaking of chemistry, this might have improved the movie: instead of casting Kline, whom Smith had no chemistry with, as Artemus Gordon, Alfonso Ribeiro, whom Smith had a shitload of chemistry with from 1990 to 1996, should have been cast as Artemus. And instead of the movie's lame depiction of Artemus as this never-convincing master of disguise Kline looked as embarrassed to be portraying as Kline's washed-up Soapdish actor character looked when he had to play Willy Loman in front of confused and senile dinner theater customers, I would have written Ribeiro's short and black Artemus as an excellent master of disguise who--because both the Wild Wild West TV show and movie never gave a shit about being authentic to the period--came up with the most effective and ludicrous-for-any-period prosthetic makeup technology for altering his looks, as well as his height, race or gender. Plus it would have been amusing to have a black guy walk around with the name Artemus.

Anyway, like Stevie Wonder, I wish that theme (BLAM!) was (BLAM!) written for a different score. There lies my problem with adding to AFOS rotation enjoyable score cues from movies that are so terrible. It's so difficult to erase those movies' wretchedness from your mind when you hear these score cues that are the only redeeming elements of those movies. So to enjoy the Bernstein score cue a little more, you just have to pretend it's not from Wild Wild West.

Man, why do post-Blazing Saddles, pre-Django Unchained westerns with black heroes have such a lousy track record? Why do sci-fi westerns that are neither the '60s Wild Wild West nor the cult favorite Brisco County Jr. have such a lousy track record? Smith and his Men in Black director Barry Sonnenfeld clearly wanted to turn Wild Wild West into a Blazing Saddles for the '90s and with splashier action sequences, except Blazing Saddles knew how to be funny.

Blazing Saddles also didn't need a $170 million budget to land its jokes. The Nostalgia Chick pointed out that Shane Black, the writer and director of one of my favorite movies, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang--a buddy comedy that, like Blazing Saddles, was able to dazzle despite a limited budget--was attached to an earlier attempt to make a Wild Wild West movie. It's one of the most interesting parts of the Nostalgia Chick's 17-minute discussion of the many things that went wrong with Sonnenfeld's Razzie sensation, including Smith rejecting the role of Neo in The Matrix and choosing to play such an unlikable and overly cocky spy.

See? This is why Ribeiro would have been a great big-screen partner for Smith: unlike Kline's snooty and stiff Artemus, the equally snooty but more underdog-ish Ribeiro--due to his chemistry with Smith--would have been able to make Smith's overly cocky Agent West more likable and relatable when they interacted with each other. It would have been like how halfway through its run, the small-town lawyer sitcom Ed gave Michael Ian Black's annoying and overly cocky Phil Stubbs character a new bowling alley boss he grew to despise, in the form of the more level-headed Eli Goggins, played by the always charismatic Daryl "Chill" Mitchell. As both Phil's foil and a character who, unlike Tom Cavanagh's rather timid Ed, had the guts to challenge Phil and bring him back down to Earth whenever Phil's antics grated on everyone's nerves, including the viewer's, Eli made Phil the myopic and self-absorbed schemer a much less annoying and one-note character for the rest of the show's run.

I also wish I were in the universe where Will and Carlton reunited on the big screen as West and Artemus. Yeah, maybe it would have been too much of a rehash of the Will/Carlton dynamic from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air for some moviegoers, but Ribeiro would have given Smith something more interesting to play against than whatever hacky shit Kline was doing. However, a completely different universe where Black's Wild Wild West got made instead is an even more enticing alternate universe. Now that is a version of Wild Wild West that would be worthy of Bernstein's main title theme. How many screenwriters did Wild Wild West have? Black's screenwriting work all by himself is frequently superior to the combined results of the 20,000 screenwriters who tried to polish the turd called Wild Wild West.

Many things doomed The Fresh Prince of Hot-Air, from its constant reshoots to skinny-pantsed '60s Wild Wild West star Robert Conrad's dissatisfaction with the script when Sonnenfeld offered him a cameo and he refused. The original Jim West bad-mouthing a reboot of his show and not giving it his blessing is like if the original Spock, when he was alive, tweeted, "I hope this new Star Trek crashes and burns," or if Michael Keaton stepped out and said, "My son showed me that new Batman trailer. Why is Ben Affleck being such a saggy diaper that leaks?" That doesn't bode well for your reboot. But when your film's key art is basically inverted key art from the 1993 megaflop Super Mario Bros., your film's really doomed.

When the only person who benefited from some part of the film is producer Jon Peters--that giant mechanical spider the extremely weird Peters kept threatening to squeeze into aborted movie versions of '90s Superman comic book storylines and Sandman finally made it into one of his productions--that's how terrible the film is. You know Patton Oswalt's six-minute distillation of the wretchedness and bloatedness of Wild Wild West (while he was being interviewed by the comedy news site/stand-up comedy record label A Special Thing)? It's six times more entertaining than Wild Wild West itself.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

Throwback Thursday: Ratatouille

Every Throwback Thursday, I randomly pull out from my desk cabinet--with my eyes closed--a movie ticket I saved. Then I discuss the movie on the ticket and maybe a little bit of its score, which might be now streaming on AFOS.

What I wrote about Ratatouille here on the AFOS blog back in 2007:

Ratatouille is a love story, but it's not your usual one. The main romance of the film is not the Linguini/Colette relationship--it's Remy the rat's love of cooking and fine dining. Giacchino's lush and playful score beautifully captures Remy's optimism and enthusiasm for the art of cooking without getting all overly gooey on us, which is why I'm adding to "Assorted Fistful" rotation four cues from the Walt Disney Records release of Giacchino's Ratatouille soundtrack.

Other things I dug about Ratatouille: the clever casting of Ian Holm, who played a similar "sellout" restaurateur character in the Deep Throat of food porn flicks, Big Night; Bird's jabs at the merchandising tactics of a certain parent company with a name that rhymes with "piznee" (during the scenes in which Holm's villainous Skinner plans to launch an inane line of frozen dinners exploiting the image of his deceased former boss, celebrity chef Gusteau); and the refreshing absence of corny and unsubtle pop culture reference gags that have been abundant in sub-Pixar animated flicks.

What I think about Ratatouille in 2015:

An unlikely box-office hit with one of the weirdest plots ever to be found in a summer blockbuster (an unusually intelligent rat's determination to become a gourmet chef), Ratatouille still holds up, and the 2008 Best Animated Feature Oscar winner will hold up forever. The DVD and Blu-ray releases of Ratatouille don't contain an audio commentary, but Baron Vaughn and Leonard Maltin's interesting Maltin on Movies discussion of why Ratatouille is such a sublime Brad Bird movie would suffice as a short commentrak for the movie ("If I see Brad Bird ever, I am going to kiss him on his mouth," jokes Vaughn), even though their 15-minute discussion, which takes place at the start of Maltin on Movies' recent "Food Movies" episode, isn't exactly scene-specific.

Bird's animated ode to culinary artistry isn't just an outstanding food movie. It's also a great Bay Area movie--even though it takes place in Paris. "The Bay Area is so obsessed with food that just finding the latest cheese, the tangiest sourdough or the richest coffee is enough to spark passionate debates," said the San Francisco Chronicle in its 2007 interview with celebrity chef Thomas Keller, Ratatouille's primary food consultant, and producer Brad Lewis about their movie. Like all other Disney/Pixar movies, Ratatouille was animated in the Bay Area, but it's the most Bay Area-esque out of all of them, because of how much Northern California's epicurean approach to food and wine suffuses Ratatouille. Pixar's location deep in the heart of the Bay Area culinary scene made the animators' culinary research really easy to access, and man, that research, which entailed cooking classes and visits to kitchens in both the Bay Area and Paris, really pays off in the movie.

Ratatouille is the quintessential family film for people like me who hate most family films. It's so enjoyably un-Disney-like--and adult--for a Disney film. Nobody bursts into a grating musical number; the film bites the hand that feeds it through its criticisms of Disney-style mass-merchandising; there's lots of dialogue about wine (in fact, Disney wanted to introduce a line of Ratatouille wines and sell it at Costco, but the studio nixed it after the California Wine Institute argued that it would encourage underage drinking); and one of the film's heroes was born out of wedlock, usually a no-no in animated Disney fare.

It builds up Anton Ego, the late Peter O'Toole's intimidating restaurant critic character, as this typical Disney villain (note how his office is shaped like a coffin, and the back of his typewriter resembles a skull face), but then it takes O'Toole's antagonist in an unexpected, completely different and believable direction. And it moves you not by killing off some child character's parent (although both of Linguini's parents are long-dead) or through some other form of misery porn. It moves you through an understated climactic voiceover, eloquently and magnificently delivered by O'Toole and nicely scored by Michael Giacchino, about the power of art and the need for critics--whether in the haute cuisine community, the film community or any other artistic community--to not be set in old ways.

O'Toole steals Ratatouille from Patton Oswalt--whose brilliant stand-up routine about overly aggressive Black Angus steakhouse ads interestingly landed him the role of Remy--whenever Ego's on screen. I especially love how O'Toole pronounces "popular" as if it's a dirty word. I wish Ego had more screen time. But then again, that's part of what makes O'Toole's performance such a highlight of Ratatouille. To borrow Ego's own words, his performance leaves you hungry for more.

Selections from Giacchino's Ratatouille score can be heard during the AFOS blocks "AFOS Prime" and "Brokedown Merry-Go-Round."

What I wrote about Ratatouille here on the AFOS blog back in 2007:

Ratatouille is a love story, but it's not your usual one. The main romance of the film is not the Linguini/Colette relationship--it's Remy the rat's love of cooking and fine dining. Giacchino's lush and playful score beautifully captures Remy's optimism and enthusiasm for the art of cooking without getting all overly gooey on us, which is why I'm adding to "Assorted Fistful" rotation four cues from the Walt Disney Records release of Giacchino's Ratatouille soundtrack.

Other things I dug about Ratatouille: the clever casting of Ian Holm, who played a similar "sellout" restaurateur character in the Deep Throat of food porn flicks, Big Night; Bird's jabs at the merchandising tactics of a certain parent company with a name that rhymes with "piznee" (during the scenes in which Holm's villainous Skinner plans to launch an inane line of frozen dinners exploiting the image of his deceased former boss, celebrity chef Gusteau); and the refreshing absence of corny and unsubtle pop culture reference gags that have been abundant in sub-Pixar animated flicks.

What I think about Ratatouille in 2015:

An unlikely box-office hit with one of the weirdest plots ever to be found in a summer blockbuster (an unusually intelligent rat's determination to become a gourmet chef), Ratatouille still holds up, and the 2008 Best Animated Feature Oscar winner will hold up forever. The DVD and Blu-ray releases of Ratatouille don't contain an audio commentary, but Baron Vaughn and Leonard Maltin's interesting Maltin on Movies discussion of why Ratatouille is such a sublime Brad Bird movie would suffice as a short commentrak for the movie ("If I see Brad Bird ever, I am going to kiss him on his mouth," jokes Vaughn), even though their 15-minute discussion, which takes place at the start of Maltin on Movies' recent "Food Movies" episode, isn't exactly scene-specific.

Bird's animated ode to culinary artistry isn't just an outstanding food movie. It's also a great Bay Area movie--even though it takes place in Paris. "The Bay Area is so obsessed with food that just finding the latest cheese, the tangiest sourdough or the richest coffee is enough to spark passionate debates," said the San Francisco Chronicle in its 2007 interview with celebrity chef Thomas Keller, Ratatouille's primary food consultant, and producer Brad Lewis about their movie. Like all other Disney/Pixar movies, Ratatouille was animated in the Bay Area, but it's the most Bay Area-esque out of all of them, because of how much Northern California's epicurean approach to food and wine suffuses Ratatouille. Pixar's location deep in the heart of the Bay Area culinary scene made the animators' culinary research really easy to access, and man, that research, which entailed cooking classes and visits to kitchens in both the Bay Area and Paris, really pays off in the movie.

Ratatouille is the quintessential family film for people like me who hate most family films. It's so enjoyably un-Disney-like--and adult--for a Disney film. Nobody bursts into a grating musical number; the film bites the hand that feeds it through its criticisms of Disney-style mass-merchandising; there's lots of dialogue about wine (in fact, Disney wanted to introduce a line of Ratatouille wines and sell it at Costco, but the studio nixed it after the California Wine Institute argued that it would encourage underage drinking); and one of the film's heroes was born out of wedlock, usually a no-no in animated Disney fare.

It builds up Anton Ego, the late Peter O'Toole's intimidating restaurant critic character, as this typical Disney villain (note how his office is shaped like a coffin, and the back of his typewriter resembles a skull face), but then it takes O'Toole's antagonist in an unexpected, completely different and believable direction. And it moves you not by killing off some child character's parent (although both of Linguini's parents are long-dead) or through some other form of misery porn. It moves you through an understated climactic voiceover, eloquently and magnificently delivered by O'Toole and nicely scored by Michael Giacchino, about the power of art and the need for critics--whether in the haute cuisine community, the film community or any other artistic community--to not be set in old ways.

O'Toole steals Ratatouille from Patton Oswalt--whose brilliant stand-up routine about overly aggressive Black Angus steakhouse ads interestingly landed him the role of Remy--whenever Ego's on screen. I especially love how O'Toole pronounces "popular" as if it's a dirty word. I wish Ego had more screen time. But then again, that's part of what makes O'Toole's performance such a highlight of Ratatouille. To borrow Ego's own words, his performance leaves you hungry for more.

Selections from Giacchino's Ratatouille score can be heard during the AFOS blocks "AFOS Prime" and "Brokedown Merry-Go-Round."

Monday, April 13, 2015

Marvel one-shot: Netflix's Daredevil contains the greatest fight scene in MCU history

Over the weekend, I marathoned all 13 episodes of Netflix's Daredevil after the streaming service unveiled all 13 on Friday. I don't call it "binge-watching." It makes watching TV sound like an eating disorder, and I don't believe in "binging" shows. TV should be savored gradually, in one- or two-episode viewings, with breaks for a meal or living life in between, instead of some extremely weird 780-minute, all-in-one-sitting session where the couch potato never showers or changes his underwear. I prefer the term "marathoning" over "binge-watching" because it sounds more proactive and productive, and it makes you feel like you've accomplished something special, like sitting through three days and two hours of Ted Mosby's obnoxiousness without ever trying to stick your head in the oven.

Daredevil follows the spy shows Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and Agent Carter as the third Marvel Studios TV show that takes place in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and is the first in a bunch of interconnected Netflix original shows that will culminate in Marvel Studios' introduction of a superteam called the Defenders to the MCU. I've never read the Daredevil comics, even though I'm a lapsed Catholic like blind lawyer/vigilante Matt Murdock, whose issues with his faith fuel much of the drama of the comics and have turned Daredevil into the most intriguing crime show about Catholic guilt since Wiseguy. I never watched either of 20th Century Fox's two pre-MCU movies featuring the Daredevil characters because the negative reviews drove me away from wasting my time with them (but I did see as a kid the not-so-good 1989 TV-movie The Trial of the Incredible Hulk, starring Rex Smith as Matt and John Rhys-Davies as Wilson Fisk, a.k.a. the Kingpin). One of those negative reviews included one of my favorite putdowns from Bay Area film critic Richard von Busack, a fan of the Frank Miller-era Daredevil comics. He wrote, "Playing blind was perfect for [Ben] Affleck, as it allowed for his customary inability to express feeling through his eyes."

Despite never seeing a single minute of Affleck's version of Daredevil, I knew early on that British actor Charlie Cox is far more nuanced and expressive than previous portrayers of Matt in this MCU version of Daredevil. There's a scene in one of the earlier Daredevil episodes where Matt, his business partner Foggy (Elden Henson) and their secretary Karen (Deborah Ann Woll, who, together with Henson, helps keep this dark show from becoming a relentlessly humorless slog) have a meeting at their struggling law firm with mob consigliere Wesley Owen Welch (Toby Leonard Moore). Cox remarkably expresses Matt's distrust of Wesley, even though his eyes are shrouded in Matt's trademark red-tinted glasses, he doesn't have any dialogue and the conversation doesn't contain any of the elaborate sound FX the show frequently relies on the rest of the time to depict Matt's heightened senses. He conveys Matt's distrust in just the way he breathes, a great early example of how genuinely mature--as opposed to Zack Snyder's idea of mature--and nuanced Daredevil is as a street-level and more grounded MCU show, as well as how surprisingly compelling Daredevil is as a legal drama, in addition to being a solid introduction to a comic book character I've never warmed up to.

Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. has often suffered from being generic-looking-as-fuck, but that's been starting to change in its second and current season, due to the increasing involvement of Kevin Tancharoen, showrunner of the not-so-generic-looking webseries Mortal Kombat: Legacy and younger brother of S.H.I.E.L.D. co-showrunner Maurissa Tancharoen, as episode director. He directed the standout S.H.I.E.L.D. episode where Agent May and an imposter posing as May fight each other. That May-vs.-May fight remains the show's best fight scene. But even the May-vs.-May showdown and the surprisingly impressive Batroc-vs.-Steve fight in Captain America: The Winter Soldier are conventional in comparison to what Cabin in the Woods director/co-writer Drew Goddard (Daredevil's showrunner for just the first couple of episodes, before Spartacus veteran Steven S. DeKnight took over), director Phil Abraham, a Sopranos cinematographer who's directed several Mad Men episodes, and stunt coordinator Philip J. Silvera pulled off for three minutes at the end of Daredevil's second episode, "Cut Man."

The single-take fight scene has been done before, but the novelty value of the single-take fight scene at the end of "Cut Man" stems from seeing it within the context of a superhero genre piece. The strengths of the MCU movies have never really been the action sequences or the fight choreography. Their strengths have always been the character writing, the snappy dialogue and the charismatic, "this is why I'm a movie star" performances from the likes of Robert Downey Jr. However, Marvel Studios seems to be starting to respond to criticisms that MCU action filmmaking is too generic and assembly-line, as exemplified by the creative freedom they gave to Shane Black for Iron Man Three (before they Britta'd things up with Edgar Wright)--Black's involvement in the MCU resulted in my favorite MCU action sequence that doesn't involve any combat, the Air Force One passenger rescue sequence--and the aforementioned Kevin Tancharoen episodes of S.H.I.E.L.D. And now along comes Daredevil, which proves in the one-shot fight scene--a moment I don't think will be up on YouTube in its entirety for too long--that it won't be another superhero genre piece where the filmmakers purposely avoid clarity during the fight scenes and let the editors and CGI FX technicians do all the work. That's the same exact complaint DVD Savant author Glenn Erickson had about the fights in The Bourne Ultimatum, which he said are "the equivalent of the dances in Chicago (2002), where every musical number is splintered into so many shots, we can't really tell if the performers can dance."

By opting for the single-take approach, Daredevil wants to show that the performers can dance, which makes the hallway fight scene so riveting to watch. "It was always scripted that this scene was going to be a one-shot," said Silvera in a New York Observer Q&A about his fight choreography for Matt and the Russian crew of child traffickers he takes down all by himself (and with the help of an unplugged microwave at one amusing point). The scene isn't just style for style's sake. The single-take approach also advances character and perfectly reflects the intensity and single-mindedness of Matt in his mission to clean up his home turf of Hell's Kitchen, as well as the difficulty of his mission (the TV-MA-rated Daredevil--which allows its characters to curse but won't allow them to say "fuck," so it'd be perfect for FX's prime-time schedule--is the first MCU project to not shy away from showing in graphic detail the wounds and battle scars its primary hero experiences). The single-take "Cut Man" fight is the show's most clever way of establishing a mission statement, and it's far better as a mission statement than any of the standard-issue "this is my city" dialogue the writers give Matt to say in later episodes.

It's great to see an MCU project taking some cues from Asian action cinema of the past 15 years. The Daredevil hallway fight is like the love child of the single-take hallway fight from another equally dark and ultraviolent comic book adaptation, director Park Chan-wook's Oldboy, and The Protector's single-take restaurant sequence, and it might remind premium-cable drama fans of the crazy six-minute tracking shot Cary Fukunaga orchestrated for True Detective last season. Fight scenes where characters are never seen getting tired and winded often bug me. That's why almost all my favorite fight scenes--whether it's the Oldboy hallway fight, the showdown in the streets between Dan Dority and the Captain on Deadwood, the brutal brawl between Lucas Hood and an MMA rapist on Banshee or the unprecedented 1970 Darker Than Amber fight where the blood all over Rod Taylor was reportedly real--are ones that emphasize the physical exhaustion of the combatants. The Daredevil hallway fight automatically shoots itself to the top of the pantheon of MCU action sequences by showing how tired Matt, who hasn't fully recovered from the injuries he sustained earlier in "Cut Man," gets while he fights his way to rescue a kidnapped boy.

Daredevil isn't a perfect show. Some feminist Marvel geeks have found most of the show's female roles to be underwhelming, even when Rosario Dawson is portraying a modernized version of Night Nurse in an intriguing nod to that non-superhero Marvel comic, and later episodes (spoilers) aren't going to impress viewers of color who complain about how the MCU shows have a tendency to opt for the POC equivalent of "women being fridged" to increase the heroes' angst. But you can't deny how Daredevil, like Arrow and The Flash's enjoyable-so-far Eobard Thawne arc before it, proves that serialized TV, when it's done right, is a better fit than a 103- or 152-minute movie for the kind of ambitious and sophisticated storytelling Clouds of Sils Maria director Olivier Assayas admires about superhero comics but has found to be lacking in superhero movies ("The movies are ultimately an oversimplification of those comic books," notes Assayas), and you can't deny the power and effectiveness of Daredevil's single-take fight. That riveting scene is an encouraging early sign of how more shades of gray are finally being introduced into the previously family-friendly and brightly lit MCU, first with the arrival of Daredevil last Friday and then with the premiere of A.K.A. Jessica Jones, the forthcoming Marvel/Netflix adaptation of Brian Michael Bendis' for-mature-readers private eye comic Alias. Now if only Daredevil had an opening title theme that's as cool and batshit--or rather, devil-may-care--as CHiPs season 1 theme composer John Parker's opening title theme for Darker Than Amber.

Daredevil follows the spy shows Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. and Agent Carter as the third Marvel Studios TV show that takes place in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and is the first in a bunch of interconnected Netflix original shows that will culminate in Marvel Studios' introduction of a superteam called the Defenders to the MCU. I've never read the Daredevil comics, even though I'm a lapsed Catholic like blind lawyer/vigilante Matt Murdock, whose issues with his faith fuel much of the drama of the comics and have turned Daredevil into the most intriguing crime show about Catholic guilt since Wiseguy. I never watched either of 20th Century Fox's two pre-MCU movies featuring the Daredevil characters because the negative reviews drove me away from wasting my time with them (but I did see as a kid the not-so-good 1989 TV-movie The Trial of the Incredible Hulk, starring Rex Smith as Matt and John Rhys-Davies as Wilson Fisk, a.k.a. the Kingpin). One of those negative reviews included one of my favorite putdowns from Bay Area film critic Richard von Busack, a fan of the Frank Miller-era Daredevil comics. He wrote, "Playing blind was perfect for [Ben] Affleck, as it allowed for his customary inability to express feeling through his eyes."

Despite never seeing a single minute of Affleck's version of Daredevil, I knew early on that British actor Charlie Cox is far more nuanced and expressive than previous portrayers of Matt in this MCU version of Daredevil. There's a scene in one of the earlier Daredevil episodes where Matt, his business partner Foggy (Elden Henson) and their secretary Karen (Deborah Ann Woll, who, together with Henson, helps keep this dark show from becoming a relentlessly humorless slog) have a meeting at their struggling law firm with mob consigliere Wesley Owen Welch (Toby Leonard Moore). Cox remarkably expresses Matt's distrust of Wesley, even though his eyes are shrouded in Matt's trademark red-tinted glasses, he doesn't have any dialogue and the conversation doesn't contain any of the elaborate sound FX the show frequently relies on the rest of the time to depict Matt's heightened senses. He conveys Matt's distrust in just the way he breathes, a great early example of how genuinely mature--as opposed to Zack Snyder's idea of mature--and nuanced Daredevil is as a street-level and more grounded MCU show, as well as how surprisingly compelling Daredevil is as a legal drama, in addition to being a solid introduction to a comic book character I've never warmed up to.

Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. has often suffered from being generic-looking-as-fuck, but that's been starting to change in its second and current season, due to the increasing involvement of Kevin Tancharoen, showrunner of the not-so-generic-looking webseries Mortal Kombat: Legacy and younger brother of S.H.I.E.L.D. co-showrunner Maurissa Tancharoen, as episode director. He directed the standout S.H.I.E.L.D. episode where Agent May and an imposter posing as May fight each other. That May-vs.-May fight remains the show's best fight scene. But even the May-vs.-May showdown and the surprisingly impressive Batroc-vs.-Steve fight in Captain America: The Winter Soldier are conventional in comparison to what Cabin in the Woods director/co-writer Drew Goddard (Daredevil's showrunner for just the first couple of episodes, before Spartacus veteran Steven S. DeKnight took over), director Phil Abraham, a Sopranos cinematographer who's directed several Mad Men episodes, and stunt coordinator Philip J. Silvera pulled off for three minutes at the end of Daredevil's second episode, "Cut Man."

The single-take fight scene has been done before, but the novelty value of the single-take fight scene at the end of "Cut Man" stems from seeing it within the context of a superhero genre piece. The strengths of the MCU movies have never really been the action sequences or the fight choreography. Their strengths have always been the character writing, the snappy dialogue and the charismatic, "this is why I'm a movie star" performances from the likes of Robert Downey Jr. However, Marvel Studios seems to be starting to respond to criticisms that MCU action filmmaking is too generic and assembly-line, as exemplified by the creative freedom they gave to Shane Black for Iron Man Three (before they Britta'd things up with Edgar Wright)--Black's involvement in the MCU resulted in my favorite MCU action sequence that doesn't involve any combat, the Air Force One passenger rescue sequence--and the aforementioned Kevin Tancharoen episodes of S.H.I.E.L.D. And now along comes Daredevil, which proves in the one-shot fight scene--a moment I don't think will be up on YouTube in its entirety for too long--that it won't be another superhero genre piece where the filmmakers purposely avoid clarity during the fight scenes and let the editors and CGI FX technicians do all the work. That's the same exact complaint DVD Savant author Glenn Erickson had about the fights in The Bourne Ultimatum, which he said are "the equivalent of the dances in Chicago (2002), where every musical number is splintered into so many shots, we can't really tell if the performers can dance."

By opting for the single-take approach, Daredevil wants to show that the performers can dance, which makes the hallway fight scene so riveting to watch. "It was always scripted that this scene was going to be a one-shot," said Silvera in a New York Observer Q&A about his fight choreography for Matt and the Russian crew of child traffickers he takes down all by himself (and with the help of an unplugged microwave at one amusing point). The scene isn't just style for style's sake. The single-take approach also advances character and perfectly reflects the intensity and single-mindedness of Matt in his mission to clean up his home turf of Hell's Kitchen, as well as the difficulty of his mission (the TV-MA-rated Daredevil--which allows its characters to curse but won't allow them to say "fuck," so it'd be perfect for FX's prime-time schedule--is the first MCU project to not shy away from showing in graphic detail the wounds and battle scars its primary hero experiences). The single-take "Cut Man" fight is the show's most clever way of establishing a mission statement, and it's far better as a mission statement than any of the standard-issue "this is my city" dialogue the writers give Matt to say in later episodes.

It's great to see an MCU project taking some cues from Asian action cinema of the past 15 years. The Daredevil hallway fight is like the love child of the single-take hallway fight from another equally dark and ultraviolent comic book adaptation, director Park Chan-wook's Oldboy, and The Protector's single-take restaurant sequence, and it might remind premium-cable drama fans of the crazy six-minute tracking shot Cary Fukunaga orchestrated for True Detective last season. Fight scenes where characters are never seen getting tired and winded often bug me. That's why almost all my favorite fight scenes--whether it's the Oldboy hallway fight, the showdown in the streets between Dan Dority and the Captain on Deadwood, the brutal brawl between Lucas Hood and an MMA rapist on Banshee or the unprecedented 1970 Darker Than Amber fight where the blood all over Rod Taylor was reportedly real--are ones that emphasize the physical exhaustion of the combatants. The Daredevil hallway fight automatically shoots itself to the top of the pantheon of MCU action sequences by showing how tired Matt, who hasn't fully recovered from the injuries he sustained earlier in "Cut Man," gets while he fights his way to rescue a kidnapped boy.

Daredevil isn't a perfect show. Some feminist Marvel geeks have found most of the show's female roles to be underwhelming, even when Rosario Dawson is portraying a modernized version of Night Nurse in an intriguing nod to that non-superhero Marvel comic, and later episodes (spoilers) aren't going to impress viewers of color who complain about how the MCU shows have a tendency to opt for the POC equivalent of "women being fridged" to increase the heroes' angst. But you can't deny how Daredevil, like Arrow and The Flash's enjoyable-so-far Eobard Thawne arc before it, proves that serialized TV, when it's done right, is a better fit than a 103- or 152-minute movie for the kind of ambitious and sophisticated storytelling Clouds of Sils Maria director Olivier Assayas admires about superhero comics but has found to be lacking in superhero movies ("The movies are ultimately an oversimplification of those comic books," notes Assayas), and you can't deny the power and effectiveness of Daredevil's single-take fight. That riveting scene is an encouraging early sign of how more shades of gray are finally being introduced into the previously family-friendly and brightly lit MCU, first with the arrival of Daredevil last Friday and then with the premiere of A.K.A. Jessica Jones, the forthcoming Marvel/Netflix adaptation of Brian Michael Bendis' for-mature-readers private eye comic Alias. Now if only Daredevil had an opening title theme that's as cool and batshit--or rather, devil-may-care--as CHiPs season 1 theme composer John Parker's opening title theme for Darker Than Amber.

Thursday, April 9, 2015

Throwback Thursday: Fight Club

Every Throwback Thursday, I randomly pull out from my desk cabinet--with my eyes closed--a movie ticket I saved. Then I discuss the movie on the ticket and maybe a little bit of its score, which might be now streaming on AFOS.

Cell phones have ruined movies forever. They've made it more difficult for screenwriters to come up with suspenseful situations. You couldn't write either Rear Window or North by Northwest today because every moment of suspense would become impossible for the nitpickers in the audience to take seriously due to "Hmm, you know he or she could use his or her smartphone to save his or her own ass in this situation." The constant advances in cell phone technology have even affected movies that have aged pretty well--when they don't involve phone scenes, that is. The appearance of any kind of phone in a largely timeless movie that's not a present-day cell phone immediately makes that otherwise timeless movie dated.

Thanks to the cutting-edge work of cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and director David Fincher, whose visuals have always been cutting-edge and distinctive (whether in Fincher-directed music videos like Aerosmith's "Janie's Got a Gun" video or more recent Fincher films like the Cronenweth-lensed Gone Girl), the 1999 anti-consumerism cult favorite Fight Club looks like it could have been filmed yesterday, and it stands the test of time--for several minutes. But then Edward Norton is seen standing in a pay phone booth to dial up his new soap salesman friend Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), and Fight Club instantly becomes dated.

I had not watched Fight Club in 16 years, before rewatching it as prep for today's edition of Throwback Thursday. In addition to containing the only film score by the Dust Brothers of Paul's Boutique fame (who really ought to compose more scores, due to their outstanding work on the 1999 film, which can be heard during either "AFOS Prime" or the first 33 seconds of the trailer below), Fight Club remains my favorite Fincher film. It's still my favorite even when the appearance of a pay phone wrecks the timelessness and anonymity both Fincher and the various adapters of Chuck Palahniuk's thought-to-have-been-unfilmable 1996 novel of the same name, including credited screenwriter Jim Uhls and uncredited Andrew Kevin Walker from Seven, tried to aim for in their portrayal of modern-day malaise (the city Fight Club takes place in is unspecified, despite the frequent use of L.A. locations, as is the name of Norton's narrator character, although the shooting script referred to him as Jack--we'll call him Jack from this point on).

Much of the appeal of Fight Club stems from the fact that we've all experienced Jack's feelings of malaise (he's nameless for a reason: so that male audience members can name the narrator after themselves). Okay, so you may not be a privileged white male yuppie like Jack, but you can definitely relate to his dissatisfaction with his job as an auto recall specialist and the feeling of emptiness that triggers his insomnia and has him doing anything to feel alive, whether it's going through an IKEA shopping phase, faking diseases and crashing support group meetings with his frenemy Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) or forming with Tyler an underground fight club to blow off steam, for men only (no Marlas allowed).

A good example of the film's ability to connect with viewers long after it tanked at the box office (Palahniuk's material isn't unfilmable--it's unmarketable, as 20th Century Fox realized while inanely trying to sell Fight Club as a TBS Movie for Guys Who Like Movies back in 1999) was when former RogerEbert.com editor Jim Emerson interestingly called Fight Club one of the most accurate depictions of clinical depression ever made and praised how it captures the way that depression is all-consuming. "It helped shake me out of the grips of a depression that was sucking me down at the time," wrote Emerson.

(Spoiler time. Weirdos who have never seen Fight Club can leave now.)

Cell phones have ruined movies forever. They've made it more difficult for screenwriters to come up with suspenseful situations. You couldn't write either Rear Window or North by Northwest today because every moment of suspense would become impossible for the nitpickers in the audience to take seriously due to "Hmm, you know he or she could use his or her smartphone to save his or her own ass in this situation." The constant advances in cell phone technology have even affected movies that have aged pretty well--when they don't involve phone scenes, that is. The appearance of any kind of phone in a largely timeless movie that's not a present-day cell phone immediately makes that otherwise timeless movie dated.

Thanks to the cutting-edge work of cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and director David Fincher, whose visuals have always been cutting-edge and distinctive (whether in Fincher-directed music videos like Aerosmith's "Janie's Got a Gun" video or more recent Fincher films like the Cronenweth-lensed Gone Girl), the 1999 anti-consumerism cult favorite Fight Club looks like it could have been filmed yesterday, and it stands the test of time--for several minutes. But then Edward Norton is seen standing in a pay phone booth to dial up his new soap salesman friend Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), and Fight Club instantly becomes dated.

I had not watched Fight Club in 16 years, before rewatching it as prep for today's edition of Throwback Thursday. In addition to containing the only film score by the Dust Brothers of Paul's Boutique fame (who really ought to compose more scores, due to their outstanding work on the 1999 film, which can be heard during either "AFOS Prime" or the first 33 seconds of the trailer below), Fight Club remains my favorite Fincher film. It's still my favorite even when the appearance of a pay phone wrecks the timelessness and anonymity both Fincher and the various adapters of Chuck Palahniuk's thought-to-have-been-unfilmable 1996 novel of the same name, including credited screenwriter Jim Uhls and uncredited Andrew Kevin Walker from Seven, tried to aim for in their portrayal of modern-day malaise (the city Fight Club takes place in is unspecified, despite the frequent use of L.A. locations, as is the name of Norton's narrator character, although the shooting script referred to him as Jack--we'll call him Jack from this point on).

Much of the appeal of Fight Club stems from the fact that we've all experienced Jack's feelings of malaise (he's nameless for a reason: so that male audience members can name the narrator after themselves). Okay, so you may not be a privileged white male yuppie like Jack, but you can definitely relate to his dissatisfaction with his job as an auto recall specialist and the feeling of emptiness that triggers his insomnia and has him doing anything to feel alive, whether it's going through an IKEA shopping phase, faking diseases and crashing support group meetings with his frenemy Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) or forming with Tyler an underground fight club to blow off steam, for men only (no Marlas allowed).

A good example of the film's ability to connect with viewers long after it tanked at the box office (Palahniuk's material isn't unfilmable--it's unmarketable, as 20th Century Fox realized while inanely trying to sell Fight Club as a TBS Movie for Guys Who Like Movies back in 1999) was when former RogerEbert.com editor Jim Emerson interestingly called Fight Club one of the most accurate depictions of clinical depression ever made and praised how it captures the way that depression is all-consuming. "It helped shake me out of the grips of a depression that was sucking me down at the time," wrote Emerson.

|

| (Photo source: DVD Beaver) |

(Spoiler time. Weirdos who have never seen Fight Club can leave now.)

Monday, April 6, 2015

I hate reunions, while I love how a little application called Adobe Premiere changed AFOS forever in 1999

|

| (Photo source: A Burger a Day) |

I don't like looking back at the past. I'd rather think about the present and the future, which is why a recent subject in this blog's Throwback Thursday series, The World's End--a cautionary film about the dangers of nostalgia and remaining in the past--resonates so much with me. Edgar Wright's film agrees a lot with me about staying focused on the future and never looking back. If I look at the blog archive at the bottom of my blog and the last few posts I wrote are all about subjects that took place before the '00s, I get really worried. "Uh-oh, I better not spend too much time in the past. Stay in the now," I think to myself. That's why I did for a couple of years a weekly series of posts about new TV (but focused on animation). Newer TV is always more fascinating to me than older TV. I don't even like film or TV blogs where the authors write only about old films or old TV, a.k.a. what Arthur Chu would call the pre-Selfie, pre-Fresh Off the Boat world. It's like those authors are basically saying, "Film and TV were better when it was all white folks." Uh, no, it wasn't, Teabagger.

This year, UC Santa Cruz--the university whose alums include Maya Rudolph, Cary Fukunaga and more recently, DJ Dahi--is celebrating its 50th anniversary. As part of the festivities, UCSC's campus radio station is inviting all former DJs, from Bullseye host Jesse Thorn to a classmate who occasionally keeps in touch with me, Yukiya Jerry Waki, to return to the station later this month and reminisce about their time there. I hate reunions and prefer to avoid them like the plague. So on some mornings in the past few weeks, I'll wake up thinking to myself, "Nah, I'll skip this Santa Cruz one." But then on other mornings, I'll wake up thinking, "Okay, maybe I'll drop by, probably tell someone a wacky story about that terrible time I did my radio show immediately after a sweaty, all-white drum circle performed live at the studio--so the studio smelled like the inside of an outhouse at a summer music festival for the rest of that afternoon--and after only a couple of hours of reminiscing, I bounce, and then it's straight to grabbing both a burger at Jack's and the next bus back north."

I'll always be grateful for what the station taught me about radio, broadcasting, chart reporting, interacting with the labels and so on--it was where AFOS began, as a two-hour show where I got the chance to interview on the phone Mark Hamill, '60s Star Trek composer Gerald Fried and my personal favorite interviewee on the phone during those UCSC years, a now-retired TV critic named Joyce Millman--but my time at the station also consisted of a few things I'm not proud of or that were just plain stupid. A reunion will just make me relive those cringeworthy moments I'd rather not revisit.

Does Bad Boys hold up 20 years after its release?

What I said about Bad Boys as an "eye Teen Reviewer" for the San Jose Mercury News back in 1995 (April 14, a week after Bad Boys' April 7 opening, to be exact), word for word and with every single Merc style guide preference preserved, straight off a clipping I still have of my own article:

'Bad Boys' is fun — for a formula movie

EYE TEEN REVIEWER

Jim Aquino

THE cop-buddy comedy "Bad Boys" (not to be confused with the 1983 Sean Penn prison pic of the same name) is the latest flashy action movie from the Simpson-Bruckheimer assembly line, which has churned out such blockbuster hits as "Beverly Hills Cop" and "Top Gun."

Directed by Michael Bay, the genius behind the popular, Clio-winning "Aaron Burr?" milk commercial, "Bad Boys" sticks to the tried-and-true formula that made Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer big-name producers back in the '80s: gaudy visuals, extravagant action sequences, a big-time soundtrack and a script that's high on concept and low on subtlety.

After producing a low-profile film such as the dark, dialogue-driven comedy "The Ref," it appears that Simpson and Bruckheimer want to go back to making big, dumb movies again. "The Ref" worked because it fit star Denis Leary's edgy, verbose persona, and never tried to soften Leary's cynical humor. "Bad Boys" could have been as satisfying as "The Ref," if its script were as clever overall as the snappy, entertaining interplay between its two leads, sitcom stars Martin Lawrence and Will Smith.

Lawrence and Smith, playing mismatched Miami police detectives Marcus Burnett and Mike Lowery, rise above the formulaic cops-vs.-heroin thieves plot to deliver top-notch performances. "Bad Boys" runs too long at more than two hours, but it remains watchable because of these charismatic, energetic stars and their fast, funny and often improvised delivery.

"Bad Boys," originally written for Dana Carvey and Jon Lovitz, is strong on visuals, thanks to first-time director Bay, who must have watched a lot of Tony Scott movies. The Miami setting is wonderful to look at, and the set pieces are well-staged.

But "Bad Boys" suffers from uninteresting bad guys and a story line that offers few surprises, aside from the amusing subplot in which neurotic family man Burnett and smooth ladies' man Lowery switch identities. Tea Leoni, who was so memorable as the sexy bohemian girlfriend on the short-lived sitcom "Flying Blind," plays a key witness.

"Bad Boys" isn't original or groundbreaking, but it's fun and entertaining, thanks to Lawrence and Smith.

What I think about Bad Boys in 2015, on the day before the date of the 20th anniversary of its release:

Of all the movie reviews I wrote for the Mercury News while in high school and then college, the mixed review of Bad Boys--at that point in his filmography, the Fresh Prince had just won over critics because of his big-screen debut in the film version of Six Degrees of Separation, but he hadn't made Independence Day yet--is one of the only two or three reviews where I still stand by every word. For instance, Michael Bay was at his best as a director of commercials like that classic "Got milk?" ad (although putting the words "Michael Bay" and "genius" in the same sentence back then makes me cringe); The Ref remains a terrific antidote to Yuletide mawkishness; and I still can't remember the name of Burnett and Lowery's boring nemesis. Like Dana Gould did when he couldn't remember the name of the villain Ben Gazzara played in Road House, I'm just going to call their boring nemesis Drago.

All the other reviews I wrote back then can go in the shredder. That was the biggest problem with being a film critic for print media. If some part of your opinion about a film would change (and my opinions sometimes do), you couldn't go back and change what you said in print like you can now easily do on a blog or in digital media.

Aside from a clunky and racist bit of attempted comedy where Shaun Toub--a.k.a. Dr. Yinsen from the first Iron Man flick--shows up as a stereotypical Middle Eastern convenience store clerk (an ominous sign of comedic things to come in Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen) who racially profiles Lawrence and Smith because of the visible guns in their holsters, Bad Boys remains one of Michael Bay's few tolerable movies. That's mainly due to the dialogue between Martin and Will ("Don't be alarmed, we're Negroes"), the most enduring part of the first Bad Boys, which cost only $17 million to make. I prefer smaller-scale Michael Bay over larger-scale, giant-robot-testicles-flashing Michael Bay, which is why I never bothered to watch 2003's much bigger-budgeted and longer-in-running-time Bad Boys II, even though Simon Pegg and Nick Frost were seen worshiping Bad Boys II in Hot Fuzz, an Edgar Wright film that trounces Bad Boys in all sorts of ways, simply because it's an Edgar Wright film (I hear 2013's Pain & Gain is supposed to be a return to Bay's smaller-budgeted roots, but I haven't seen that one yet either).

The Bad Boys original score by Mark Mancina still holds up too and hasn't aged poorly at all. During "AFOS Prime" and "Beat Box" on AFOS, you can hear a previously unreleased version of the film's dancehall-influenced main title theme, Mancina's "Prologue - The Car Jacking," taken from La-La Land Records' out-of-print Bad Boys score album and featured below. (The Bad Boys song album's not too shabby either. I remember practicing to get my driver's license to the sounds of Diana King's dancehall-style "Shy Guy.")

If you still find Bad Boys--or Drago--to be too generic for your tastes, perhaps reading Shield creator Shawn Ryan's mostly sardonic live-tweets of Bay's Bad Boys DVD commentary while he watched Bad Boys for the first time ever in 2012 will make the film go down easier. "Michael goes silent on commentary for a few minutes," tweeted Ryan, who actually likes the movie, during a lull in Bay's pontifi-bating. "Perhaps he took a break to write nasty email to Megan Fox."

Thursday, April 2, 2015

Throwback Thursday: Short Term 12

Every Throwback Thursday, I randomly pull out from my desk cabinet--with my eyes closed--a movie ticket I saved. Then I discuss the movie on the ticket and maybe a little bit of its score, which might be now streaming on AFOS. This week, I drew the ticket that said "Thor." But I feel like I've said all I could say about the first Thor movie in my discussion of Thor: The Dark World a couple of weeks ago. Also, I'm tired of talking about superhero movies. So I'm ditching the movie I drew--it's my blog, I can do what I want--and focusing my attention this week on a smaller-scale movie about a completely different kind of hero. Even after its release two years ago, it still deserves as much attention as the kind a superhero movie always gets from the press before its release, and if you're not familiar with this little movie, familiarize yourself with it now on Netflix streaming.